In the early years of the epidemic, neurological problems—dubbed neuro-AIDS—were a major concern. HIV can damage the brain directly, and several opportunistic infections can cause neurological symptoms. According to some estimates, as many as half of all people with AIDS developed debilitating brain problems.

Today, severe neurological manifestations of HIV are less common thanks to effective antiretroviral treatment. Nonetheless, people living with the virus may experience more subtle neurological and cognitive problems, collectively known as HIV-related neurocognitive disorder (HAND). Even when viral load is undetectable, HIV can cause chronic immune activation and inflammation that take a toll on the brain. What’s more, the aging HIV population is prone to the neurocognitive decline that comes with advancing age.

It is unclear how many people are affected by HAND. Studies have produced widely varying estimates, in part because they use different definitions of the condition. But we know that HIV-related neurocognitive problems are more common among people with uncontrolled virus and advanced immune suppression, as indicated by a low CD4 T-cell count.

What kinds of neurological problems affect people with HIV?

Before effective antiretroviral therapy was available, HIV caused serious neurological conditions, including HIV-associated dementia, also known as AIDS dementia complex. People with advanced immune suppression were at risk for life-threatening brain infections, such as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, toxoplasmosis and cryptococcal meningitis. These opportunistic infections are now uncommon in the United States, but they still may occur among people who aren’t on effective antiretroviral treatment.

Yet despite treatment, people living with HIV may still experience problems with thinking, concentration, memory, learning, verbal fluency, mood, sleep and, in some cases, physical coordination and mobility. These can range from mild forgetfulness and brain fog (slowed thinking and poor concentration) to more debilitating cognitive impairment. In many cases, these deficits are subtle enough that they do not affect daily life and can only be detected with special tests.

More than half of people living with HIV are over age 50, meaning age-related neurocognitive problems—from increased forgetfulness to Alzheimer disease and other forms of dementia—are a growing concern. Some evidence indicates that HIV-positive people may experience age-related cognitive decline earlier than their HIV-negative peers. But age-related changes in cognition and memory are normal, and it can be hard to tease out the specific effects of HIV.

What causes HIV-related neurocognitive disorder?

Many factors can contribute to neurological and cognitive problems among people living with HIV. These include a high viral load, low CD4 count, AIDS-related illnesses, non-AIDS comorbidities (such as hepatitis C, diabetes and cardiovascular disease) and depression or other mental health issues. Alcohol and drug use can also play a role.

HIV can enter the brain, and studies have shown that this may happen within days after initial infection. HIV appears to damage neurons (nerve cells) and other types of support cells in the brain, although researchers don’t fully understand how this happens.

Neurological and cognitive problems typically worsen over time, especially if the virus remains unsuppressed, highlighting the importance of starting antiretroviral treatment as soon as possible after diagnosis. But even among people on antiretrovirals, HIV can trigger persistent systemic inflammation that contributes to problems throughout the body, including cardiovascular disease, cancer and cognitive impairment. What’s more, long-term survivors who acquired HIV before the advent of effective antiretrovirals may have lingering neurocognitive problems.

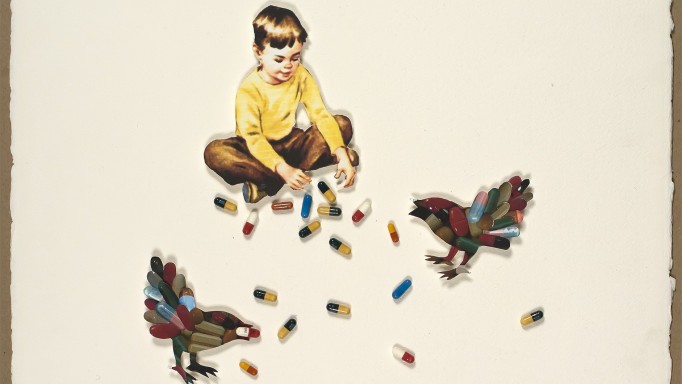

Some antiretrovirals, as well as medications for other conditions, can cause neuropsychiatric side effects, such as brain fog, mood changes and sleep problems. Among HIV meds, efavirenz (Sustiva) has been most often associated with mental side effects.

Can HIV-related neurocognitive problems be prevented?

While it may not be possible to prevent HAND entirely, you can take steps to keep your brain sharp and improve your overall neurological health.

The first step is starting and staying on antiretroviral treatment to keep your viral load undetectable. Some HIV medications can cross the blood-brain barrier that protects the brain and spinal cord. Although it was once considered important to select meds that reach the brain, modern antiretrovirals can control HIV throughout the body.

Managing other conditions that can contribute to worsening brain function is also key. This includes treating coexisting diseases, such as hepatitis C, and controlling high blood pressure and elevated blood sugar and lipid levels. If you smoke, try to quit, and limit use of alcohol and drugs. Exercising, eating a balanced diet, maintaining a healthy weight and getting enough sleep are all important for overall health, including the health of your brain.

Research shows that staying mentally active throughout life can help stave off cognitive decline. This may include doing puzzles, playing memory games, reading, taking classes or learning a new language—anything that stimulates your brain and keeps your mind sharp. Social engagement is also important, for example, socializing with friends, participating in hobby or sports groups, attending religious services or volunteering. If you’re unable to get out of the house easily or live in a rural area without many social opportunities, you can connect with others online. Check the POZ Forums and begin connecting with others today.

How are HIV-related neurocognitive problems managed?

Let your health care provider know if you experience changes in thinking, concentration, memory, mood or other neurocognitive symptoms, especially if they are getting worse over time. It may be helpful to document such symptoms in a diary.

Your doctor will try to rule out other causes of cognitive symptoms before settling on a diagnosis of HAND. Tests may include mental status exams (game-like tests to check cognition, verbal ability, short- and long-term memory and concentration); CT scans, MRI or other imaging of the brain and spinal cord; and spinal taps (lumbar punctures) to analyze cerebrospinal fluid. If HAND is suspected, it may be helpful to consult a neurological specialist familiar with HIV.

There are many tips for coping with poor concentration and memory. These include writing reminder notes or recording memos on your phone, keeping weekly and monthly checklists to help you remember important errands and bills you need to pay and using a pill organizer to sort your medications. Don’t hesitate to ask friends or family members for support and assistance.

Cognitive rehabilitation or occupational therapy may help with more serious problems, especially after a brain injury. In some cases, medications can help improve mood or concentration, but treatments for dementia are limited and only modestly effective.

Despite decades of research, much remains to be learned about neurological and cognitive problems among people living with HIV. For example, it is not yet known whether people with mild cognitive symptoms are at greater risk for progression to dementia. The picture will likely become clearer with more research as the HIV population ages. Ask your provider or visit ClinicalTrials.gov to find studies that aim to learn more about HIV-related neurological problems and develop new treatments.

Last Reviewed: January 7, 2025