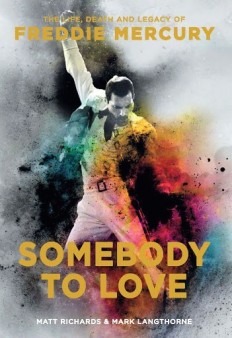

HIV plays a prominent role in Somebody to Love: The Life, Death and Legacy of Freddie Mercury, the biography of the rock icon and Queen front man who died of AIDS-related illness in November 1991 at age 45. Authors Matt Richards and Mark Langthorne pack the book with behind-the-scenes details of the band’s megahits—“Bohemian Rhapsody,” “We Are the Champions,” its Live Aid performance in 1985 and much more. POZ spoke with Langthorne about the biography’s AIDS angle; read the full interview on POZ.com.

Your book reads almost like two parallel bios—one of Mercury and another of HIV. The book even starts in 1908, with the birth of the AIDS epidemic. Why structure the book this way?

Mercury in Rio de Janeiro in 1985Courtesy of Weldon Owen/Richard Young

I’m a fan of Freddie Mercury and a gay man who lived through the ’70s and ’80s, so it seemed an opportunity to combine both subjects in a unique way. We wanted Queen fans to pick up the book and learn something about the times, the individual and his personal struggle.

Mercury never publicly acknowledged he had sex with other men, and he didn’t disclose his HIV to many of his closest friends until it was impossible not to. Today, some folks consider that silence to be cowardly. How would you respond to such accusations?

We judge the past from a different present. In the book, we try to understand how Freddie became who he was, his background and upbringing, the times, the homophobia, the vile British press [that tried to out him as gay and living with HIV], the members of Queen and the pressures not just on him but for all those people around him who relied on the industry that Queen had become. It was never a case of Freddie coming out as gay and telling the world he was HIV positive and then getting on with his life. It was never going to happen. The times he lived through were corrosive and bitter.

You pinpoint a moment when Freddie was likely exhibiting signs of acute HIV infection, which refers to the few months directly after an individual contracts the virus. That moment was Queen’s 1982 performance on Saturday Night Live, singing “Under Pressure” and “Crazy Little Thing Called Love.” It’s fascinating sleuth work, but why figure that out?

Courtesy of Weldon Owen/Wendy Allison

He claimed he was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in 1987, but when you later learn that in fact he was likely infected five years earlier, you see a different person than the one you thought you saw. You see a person fighting. It also gives us insight into the times, and I suppose a clearer snapshot of his life.

Let’s talk about Gaëtan Dugas, a.k.a. Patient Zero, the man incorrectly vilified as having spread HIV throughout America. He and Freddie met a few times; they shared a common lover as well as many parallel experiences in life and death. At times, I read this section almost as if Mercury himself were a patient zero. When asked if he altered his sexual behavior once AIDS hit, Mercury says, “Darling, fuck it, I’m doing everything with everybody.” What are we to make of this?

What do you want to make of it? So many of us dealt with [the AIDS crisis] in different ways—after all, there was no template then. There was no right or wrong in this. It cannot be a moral judgment. Now we can make fully informed choices [about HIV risks], but that was not the case then. We clung on to how far we had come by the early ’80s socially, politically, sexually; and then suddenly, this thing called AIDS threatened to take it all away, and then it did.

What aspect of Freddie Mercury surprised you while you researched this book?

The difference between the performer and the showman, and the individual and the star. Offstage he seemed somehow diminished. When I met him, I found a shy, self-conscious, awkward man, who required drink and drugs to open up. There was a sadness to him, a kind of defense mechanism, the sort that keeps even the richest man poor.

I had never heard that “Bohemian Rhapsody” had a hidden meaning. Can you elaborate?

Courtesy of Weldon Owen/Wendy Allison

During his lifetime, Freddie never revealed what “Bohemian Rhapsody” was about. While many took it at face value, thinking it was about a murderer confessing to his crime, other analysts point to it being an illustration of his emotional mindset during that period. At the time of writing the song, he was already embroiled in an affair with David Minns despite living with Mary Austin. Queen’s manager at the time was John Reid, and in an exclusive interview for the book, he says, “I subscribe to the theory…that it was his coming out song.” Others agree: Lyricist Sir Tim Rice says, “I heard the record very early on, and it struck me that there is a very clear message contained in it. This is Freddie saying, ‘I’m coming out. I’m admitting that I’m gay.’” It’s possible to create a homosexual subtext to virtually any phrase from the song. For example, “Mama, just killed a man” is not necessarily about the criminal act of murdering someone but more the metaphorical act of killing his old self, the heterosexual man.

Talks of a Queen biopic are once again making headlines, this time with Mr. Robot star Rami Malek as Mercury. What are your thoughts on the role that gay sexuality and HIV should play in the film?

I understand [the film] will not be dealing in depth with Freddie’s sexuality or his death, which seems to me to be missing the point. After all, he was one of the most famous casualties of AIDS, and his death and life are inextricably linked.

Comments

Comments