Once the glass doors to the clinic open at 10 A.M. sharp, dozens of people file in from San Francisco’s Castro Street. Decked out in dressed-down West Coast chic, these super hip Bay Area residents, a mix of transgender women and men who have sex with men (MSM), are taking steps to care for their sexual health.

“It’s the procession,” remarks Jayne Gagliano, who sports a no-nonsense bob and has on skintight stretch pants. She’s the benefits manager at this new LGBT-focused sexual health and wellness clinic. It’s her job to fight for those seeking Truvada (tenofovir/emtricitabine) as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV, helping them secure insurance coverage or tap into other available sources of payment. Her role is crucial; a month’s supply of Truvada costs upwards of $1,200.

The three-story clinic is called Strut. Considering the cocksure air of the clientele, the name fits. An offshoot of San Francisco AIDS Foundation with an $8.5 million annual budget, Strut is the new home of the SFAF PrEP program.

Since launching in November 2014, this PrEP initiative has provided Truvada to 800 HIV-negative individuals—a group made up largely of white MSM at high risk for HIV. Some drive as long as two hours to get to the clinic. The draw is sexual health services that are not only free but also provided by a sex-positive, nonjudgmental staff—or, in the words of this town’s hippie anthem, by “gentle people with flowers in their hair.”

No one in the PrEP program has contracted HIV.

The symbolism of Strut’s location is inescapable. Situated across from the famed Castro Theatre, it’s in the heart of San Francisco’s storied gay neighborhood. There’s a fog of painful memories here, of the crisis era of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and early ’90s. Strut is confronting that history head-on.

Strut stands at the vanguard of San Francisco’s all-hands-on-deck mission to be the first municipality to effectively halt HIV transmission. The city recently launched a multipronged HIV-fighting campaign called “Getting to Zero,” in which the members of local academia, the public health department and community-based organizations, as well as government officials and health care providers, are working in lockstep.

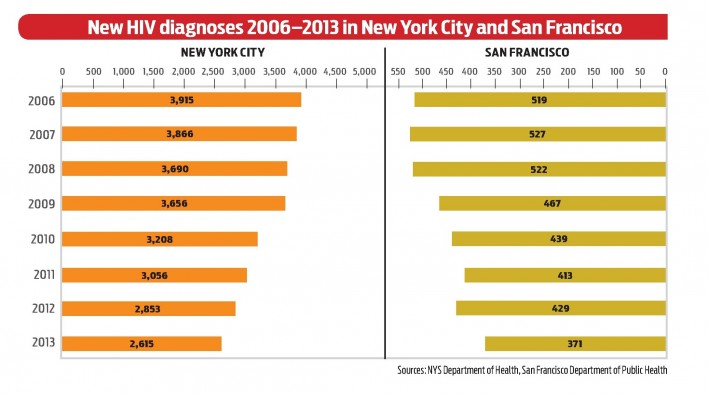

Their primary goals are to bring the annual HIV diagnoses below 50 and to greatly reduce deaths among HIV-positive people by 2020. Diagnoses already dropped from 519 in 2006 to 302 in 2014, while annual deaths among the estimated 16,000 HIV-positive San Franciscans fell from 327 to 177.

Meanwhile, the major players in New York’s epidemic have formed a similar alliance. Home to 80 percent of the state’s HIV-positive population of about 129,000 people, New York City is partnering with the state government on a sprawling plan called the Blueprint to End the AIDS Epidemic. The hope is that the state’s annual HIV diagnoses, which fell from 4,600 to 3,500 between 2009 and 2013, will drop to 750 by 2020.

Biomedical HIV prevention—using antiretroviral (ARV) drugs to prevent transmission—is at the core of each city’s strategy. Since 2011, studies have suggested that successful treatment all but eliminates the risk of an HIV-positive person transmitting the virus; this is known as “treatment as prevention,” or TasP. Then there’s PrEP, approved in 2012. When taken daily, Truvada reduces HIV risk by an estimated 99 percent. These insights enabled a new era in the HIV fight.

San Francisco’s falling HIV rate is in part a by-product of a 2010 stance by local officials: to treat the virus as soon after diagnosis as possible. More people on HIV treatment meant fewer could readily transmit. The city was the first to make this policy shift, which went national in 2012. Taking the stance meant going out on a limb, because gold-standard scientific evidence was still lacking to support early versus delayed HIV treatment. Such evidence came from a randomized controlled trial in May 2015, vindicating San Francisco’s bold move.

Supervisor Scott Wiener represents San Francisco’s Castro District, which has been hard hit by HIV. He’s one of the key political proponents of the Getting to Zero campaign in City Hall—not that he faces any particular adversaries on this front within the highly progressive chamber.

“People are genuinely excited,” says the lanky, soft-spoken Wiener, “that after all these years in defense, we’re now able to go on the offensive and visualize a collapse in infection rates. And perhaps even eliminate new infections.”

The genesis of each city’s epidemic-ending plan traces from the 2012 International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2012) in Washington, DC, which was cochaired by Diane Havlir, MD, chief of the HIV department at San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH). During a postconference forum in San Francisco, an audience member asked her how the city’s HIV leaders were working together to combat the local epidemic.

“It was that moment we just realized we could be working together,” a serenely pleasant Havlir recalls in her sunny corner office in Ward 86, SFGH’s HIV wing, which was ground zero for local AIDS care in the 1980s.

“We were working in silos at the Department of Public Health [SFDPH] and at UCSF,” says Susan Philip, MD, MPH, director of disease prevention at SFDPH. “Everyone had a history of activism and innovation, but there had not been a coordinated effort.” (Philip is a member of an elite triumvirate of like-named women at SFDPH, including Susan Buchbinder, MD, director of an HIV prevention research unit, and Susan Scheer, PhD, MPH, director of HIV epidemiology.)

New York’s own effort got started in a jail cell. Mark Harrington, executive director of Treatment Action Group, and Charles King, president and CEO of Housing Works, were locked up in a DC pen for committing civil disobedience during the AIDS 2012 conference. Disappointed with the Obama administration’s HIV efforts, they began to envision a bold push to control New York State’s epidemic.

Following these revelations, the HIV communities in each city assembled stakeholders and began drafting plans. Both groups aimed to leverage the improved access to health care promised by the imminent rollout of the Affordable Care Act. They also envisioned ways to fill in the gaps in health care access that the legislation would leave, paying particular attention to historically disenfranchised groups, including racial and ethnic minorities, transgender women, injection drug users (IDUs) and the homeless and unstably housed.

San Francisco’s Getting to Zero Consortium announced its core strategies in 2014 and began implementation in 2015. PrEP promotion among at-risk individuals is high on the list. On the linkage-to-care front, a positive HIV test result starts a process that can get a person on meds within 72 hours. (New York hopes to emulate this model in the near future.) Additionally, the city’s top-notch HIV surveillance apparatus is guiding a ramped-up effort to keep people with HIV in consistent care. Reducing HIV-related stigma and health disparities between key demographics are further goals.

Flush with tech boom dollars, San Francisco has been able to replace about $20 million in cumulative lost federal HIV funding since 2011. Wiener, who made national headlines when he came out publicly in 2014 as taking PrEP, recently helped lead the push at City Hall to add $1.7 million, including $500,000 from MAC AIDS Fund, to the city’s annual HIV-related budget, which is currently $58.5 million.

Thanks to expanded testing for the virus in recent years, an estimated 93 percent of the city’s HIV-positive residents knew their serostatus in 2013. At that time, 69 percent of San Franciscans with HIV were receiving regular care, 64 percent were on treatment and 60 percent were virally suppressed.

By comparison, New York has more work to do. Only an estimated 43 percent of HIV-positive New York City residents were virally suppressed in 2013, although this figure is rising.

The New York plan is laid out in a 70-page progressive manifesto that includes 30 recommendations for improvements to the state’s HIV testing, treatment and prevention infrastructure. The 2015 document is less focused than its San Francisco counterpart, and at points it amounts to more of a wish list than policy with actual hopes of passage.

Additionally, the New York plan’s financial backing is as uncertain as its price tag is undefined (authors have floated estimates, but it lacks a line-item budget). The governor has held the keys to the coffers close. The New York City Council, however, passed $3.9 million in new annual funds, and the mayor’s office pledged $23 million in new money. The state is securing rebates on meds from pharmaceutical players. It also passed a rent cap for HIV-positive New York City residents receiving housing assistance-—they can’t pay more than 30 percent of their income in rent.

For the 2015 to 2016 fiscal year, New York State gave only an additional $10 million specifically for the blueprint’s goals, a figure King calls “a drop in the bucket.” But then, Governor Andrew Cuomo, who had heartily endorsed the plan at a springtime ceremony, announced a pledge of $200 million in backing at a World AIDS Day event in December 2015, adding to the state’s $2.5 billion annual HIV budget.

“We couldn’t believe it,” says ACT UP veteran and one of the blueprint task force’s 60-plus members Peter Staley. In early 2016, the governor clarified he actually intended to spread the new money over five years. Ultimately, his current annual budget provided only another $10 million in additional funds.

“In what world does a $200 million pledge become only $10 million spent?” says Staley. “This is not how you end an epidemic.”

San Francisco has an easier task of achieving its own HIV-related ambitions. A much smaller city, its epidemic is a fraction of New York’s. San Francisco’s epidemic is also largely homogenous, making it simpler to tackle. Almost 90 percent of HIV-positive residents are MSM, and two thirds are white or Asian and Pacific Islanders. However, as local diagnoses have declined among whites and blacks, a disproportionate number of Latinos are testing positive.

New York State’s epidemic is more diverse, both in its racial makeup and modes of transmission. Twenty-one percent of new diagnoses are in women, mostly black and Latina. Furthermore, New York City’s epidemic has starkly different characteristics in each of the city’s five boroughs, requiring a public health approach differently tooled for each area.

“We’re like five cities, in fact,” reflects Demetre Daskalakis, MD, MPH, New York’s assistant commissioner of the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control.

A major challenge facing New York State is bringing down its stubbornly stable HIV diagnosis rate among MSM. All other major risk groups have seen a steady decline in diagnoses for many years, including men and women who contract HIV through heterosexual sex. No child has been born with the virus in the state since August 2014. Also, syringe exchange programs and other harm reduction endeavors have slashed diagnosis rates among IDUs by 96 percent since the mid-1990s.

The issue of housing looms over New York and San Francisco alike. Included in New York’s blueprint are highly ambitious goals for providing rental assistance to thousands of homeless or unstably housed HIV-positive people. The estimated price tag starts at $83 million per year and could grow to $130 million by 2020. Such substantial figures question the feasibility of the housing goals, given the financial cold shoulder from Cuomo. San Francisco is addressing housing in the second phase of Getting to Zero’s implementation.

“Housing equals health care,” stresses openly HIV-positive New York City Councilman Corey Johnson. (People with HIV who lack a stable home are less likely to be virally suppressed.) Johnson is Wiener’s East Coast counterpart, representing a large gay population and serving as an HIV advocate locally.

“We are living in a city where it takes one month of unemployment for someone to end up on the street,” says Blair Turner, a nurse practitioner at San Francisco’s Asian & Pacific Islander Wellness Center, a federally qualified health center in the city’s economically strained Tenderloin District. The center largely serves LGBT racial and ethnic minorities, with a strong emphasis on trans care.

***

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported that annual HIV diagnoses fell 19 percent in the United States during the last decade. But national tides don’t necessarily drive local epidemics; the opposite is largely true. New York’s and San Francisco’s success in driving down diagnoses is intricately tied to active local public health efforts. Cities and states with more fragmented, or woefully lacking, HIV-fighting initiatives have not necessarily followed the national trend. This is particularly true in the South.

Stakeholders in both New York and San Francisco are hoping PrEP will drive down HIV rates among MSM and trans women in particular. New York State has established a program to assist with non-medication-related PrEP costs.

Sources suggest that PrEP use has surged in the past two years among MSM in both cities, with those at higher HIV risk more inclined to take Truvada. In one recent analysis of national surveys of MSM taken between late 2014 and early 2015, 17 percent of respondents in San Francisco and 12 percent in New York reported that they took Truvada for prevention.

The shaved-head, slickly bearded Daskalakis has given a youthful jolt to New York’s HIV fight, thanks to his public health savvy and sassy, queer street smarts. He was instrumental in developing the city’s HIV prevention campaign “Play Sure,” which winks that pleasure is paramount in sex. The flirty, multiracial, LGBT-friendly campaign establishes PrEP, condoms and HIV treatment as the three pillars of prevention.

“We’re going to set the place on PrEP fire,” says Daskalakis, pointing to plans for a system of PrEP promotion at New York City’s public clinics for sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

But, recently the city has seen STI clinic closures, some of which are temporary and for much-needed renovations. And in 2015, ACT UP member James Krellenstein and his fellow activists uncovered budget cuts and a drop in HIV screening in the clinic system. The resulting activist outcry prompted by Krellenstein’s disclosure—he says he’s “just shocked” that the blueprint task force had failed to discover this information—prompted the city to begin dialing back the cuts.

It’s too early to tell how PrEP may be affecting HIV rates in either New York or San Francisco, but the signs are hopeful. According to C. Bradley Hare, MD, the director of HIV care and prevention at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in San Francisco, the clinic’s PrEP program, now 1,400-people strong, has seen no HIV cases despite a very high STI rate. However, two people who dropped out because of changes in their insurance and health care providers did test HIV positive. Hare says these two cases underline the importance of ensuring a continuity of both care and coverage to those on PrEP.

Then there are the missed opportunities. Antonio Urbina, MD, an HIV specialist at Mount Sinai Hospital’s expansive HIV practice in New York City who increasingly prescribes PrEP, recalls an HIV-negative patient who came in for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after a high-risk sexual encounter. Urbina encouraged the young gay man to consider PrEP.

“‘I don’t want to take it; it’s going to make me sluttier,’” Urbina recalls the man responding. When the patient returned for follow-up after his month on PEP, Urbina kept trying to pique his interest in Truvada. Six weeks later, the man returned. Urbina was excited, presuming he had persuaded him to go on PrEP. The man said he had tested HIV positive. “I felt awful,” says Urbina. “I passed blame and judgment on myself.”

Health care providers invested in PrEP are striving to find the magic formula to promote its use, while those caring for people living with HIV try to keep them in regular medical care. Urbina’s clinic is among those receiving city funding for a highly involved, and expensive, program to identify HIV-positive people at risk of falling out of care. They also conduct searches to track down people who have fallen out of care.

Montefiore Medical Center, located in New York’s racial-minority-dominated Bronx borough, has spent decades gaining trust in the community, which got the cold shoulder from the city’s health department in the 1960s and ’70s, to ruinous effect. Viraj Patel, MD, MPH, an internist and researcher at Montefiore, says that the center began PrEP trainings for everyone at its network of primary care health centers—from clinicians to front desk staff.

***

As the epidemic moved into a postcrisis era during the aughts and donations to HIV-related nonprofits tapered, “AIDS isn’t over” became a popular fundraising slogan. Today, that slogan has often been replaced by a new message, which essentially says: “AIDS will soon be over.” Definitions of that end—there is no official scientific definition—are often arbitrary or defy logic.

Krellenstein picks apart the New York blueprint’s definition of the state epidemic’s end: when annual number of deaths exceeds the number of new infections—750 is the target figure—and the HIV population contracts. “In 1995, more U.S. AIDS patients were dying than were getting newly infected,” quips the fast-talking Krellenstein, who has an encyclopedic knowledge of HIV. “That didn’t mean the epidemic was over then either. This 750 point is dangerous,” he adds, “because it will convince us we’ve ended something we haven’t.”

Should the white flag wave, about 130,000 people in New York State and 16,000 in San Francisco will still be living with the virus. “We’re still going to have the problem of keeping people engaged in their care over a lifetime,” says Darpun Sachdev, MD, the medical director of San Francisco’s program to link people into care and keep them engaged.

What if the public moves on once the predefined terms of victory have been met? “There is a fear that our funding will decrease,” says Tracey Packer, MPH, director of community health equity and promotion at SFDPH. “To maintain zero, or at least a low number, funding has to continue at current level.”

***

As each city makes strides in controlling HIV, will they be writing the rule book for other areas? Or will their successes prove exceptions to the rule? Leaders in each effort are striving to share their wisdom with others; but, of course, success doesn’t come cheap. “When I travel around the country, I’m in awe of the riches that we have in New York State,” says Daskalakis.

SFDPH’s Susan Philip says that her counterparts in different locales may question the exportability of San Francisco’s HIV-fighting model. Still, achieving the Getting to Zero goals would be “incredibly valuable as a proof of concept,” she says.

“My hope is that, as more places do it, the effort will really build on itself, build momentum,” says Glennda Testone, executive director of New York’s LGBT Community Center and a blueprint task force member. She imagines numerous local epidemics reaching a collective tipping point.

Peter Staley reflects on the significance of such success. “It could be real legacy stuff,” he says. “This is our endgame.”

Editor’s note: At the final hour of the New York State legislative session at the end of June, Governor Cuomo announced an expansion of housing benefits to low-income residents living with HIV. The State will give about $31 million per year to the program, while the city’s contribution will be about $52 million during the first year and $89 million the following year.

3 Comments

3 Comments