The early days of AIDS were marked by fear fueled by ignorance. Thankfully, much has changed since the introduction of effective treatment in 1996. Millions of lives have been saved in the United States and around the world. Nonetheless, HIV stigma remains pervasive, even earning its own section in the National HIV/AIDS Strategy.

Although negative and unfair beliefs about HIV/AIDS aren’t as openly expressed by most people as they used to be, current beliefs are stubbornly similar to those of years ago. For example, a 2011 Kaiser Family Foundation study found that, despite decades of education efforts, much of the public remains uncomfortable with HIV-positive people.

Advocates acknowledge that fighting stigma isn’t easy—it’s like battling the Hydra monster of Greek mythology: Chop off one head of the dragon-like serpent, and two more grow back. Some even argue that stigma has mutated and is worse today than ever, at least among gay men, but possibly in general.

“Stigma is somewhat like smoke—you know it’s there, but it’s difficult to see and hold on to,” says David Ernesto Munar, president and chief executive officer of the Howard Brown Health Center, which serves the LGBT community in Chicago. “It’s a major driver in perpetuating the epidemic.”

Munar believes that stigma results in harm to everyone—people living with the virus, as well as those who are negative or of unknown status. As a person living with HIV, and the former head of the AIDS Foundation of Chicago, he has had a front-row seat. “People might not get the HIV testing they need,” he says. “They might lose their income, housing, family and friends.”

There are many ways to combat the illegal discrimination that results from stigma (Click here to read “Defying Discrimination” for details). However, the methods to stem stigma itself seem more elusive. Educating with one-to-one discussions perhaps remains the best, but many advocates continue to pursue more widespread methods, such as awareness campaigns. The most recent example is titled “Start Talking. Stop HIV.” Launched in May by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it encourages gay and bisexual men to communicate with their sexual partners about HIV risk and prevention strategies. It includes online and print advertisements, social media engagement and online videos.

The most recent example is titled “Start Talking. Stop HIV.” Launched in May by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it encourages gay and bisexual men to communicate with their sexual partners about HIV risk and prevention strategies. It includes online and print advertisements, social media engagement and online videos.

This campaign is part of the CDC’s Act Against AIDS initiative, which includes Let’s Stop HIV Together, a general awareness campaign; Greater Than AIDS, a campaign targeting African Americans; Testing Makes Us Stronger, a campaign targeting African-American gay and bisexual men; and Reasons/Razones, a campaign targeting Latino gay and bisexual men.

The CDC’s focus on gay and bisexual men is no surprise. Men who have sex with men (MSM), especially MSM of color, are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS. Further, new HIV cases among MSM are increasing as they flatten or even fall among other groups. Advocates blame HIV stigma among MSM, which they claim has created a “viral divide.”

This divide is probably the most evident on social networking apps and hookup sites. Phrases such as “DDF UB2” (short for “drug and disease free, you be too”) and questions such as “Are you clean?” have become commonplace. Many HIV-positive gay men note anecdotally that when they challenge HIV-negative men about such language (“Does having HIV make me ‘unclean’?”) the responses (“Whatever!”) are often filled with contempt.

“The more HIV treatments improved, the wider the viral divide became,” says advocate, author and blogger Mark S. King in his essay “The Sound of Stigma” from the June 2013 issue of POZ. “From whatever our vantage point, we have shamed and stigmatized everyone else into a corner, and the result is a community in revolt against itself.” The essay touched off a firestorm of response, proving it hit a raw nerve among gay men.

Peter Staley, founder of AIDSmeds and a veteran activist featured in the Oscar-nominated documentary How to Survive a Plague, picked up the discussion this past February. “HIV-related stigma is worse than ever,” he says in his entry “Gay on Gay Shaming: The New HIV War” on The Huffington Post (and crossposted to his POZ blog). “It breaks my heart that the worst of HIV stigma comes from my own community: gay men.”

“Stigma today isn’t about [being afraid of] casual contagion like it was in the 1980s. It’s about making a snap judgment on the moral character of the individual who is HIV positive,” says Sean Strub, founder of POZ and executive director of the Sero Project, which fights stigma and injustice with a current focus on HIV criminalization. “Today’s stigma is prejudgment and marginalization. ‘Were you going to the baths? Were you using crystal meth?’” HIV stigma among MSM is a hot topic, but stigma affects all groups, including women. “I’ve been living with HIV since 1993, and stigma hasn’t changed much,” says Shari Margolese, a research consultant in Ontario, Canada, and a peer educator with the Positive Women’s Network (PWN), an international group. “People always want to know how you became positive. There has been a movement to define ‘good’ and ‘bad’ HIV-positive people.”

HIV stigma among MSM is a hot topic, but stigma affects all groups, including women. “I’ve been living with HIV since 1993, and stigma hasn’t changed much,” says Shari Margolese, a research consultant in Ontario, Canada, and a peer educator with the Positive Women’s Network (PWN), an international group. “People always want to know how you became positive. There has been a movement to define ‘good’ and ‘bad’ HIV-positive people.”

In 2013, PWN-USA released the findings of a study on gender-based stigma and violence. Margolese was one of the co-authors. Seventy-two percent of positive women surveyed experienced intimate-partner violence, as opposed to a quarter of all women. Seventy percent had been sexually assaulted, compared with 20 percent of all women. Many women also expressed changes in perceptions of their body image and sexual desirability.

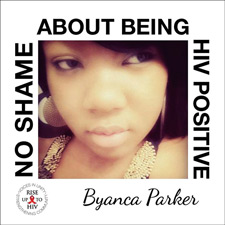

“Stigma toward HIV-positive women presents itself in many ways, including perceptions that you cannot have children or sex,” says Byanca Parker, a 21-year-old activist from Dallas. Born with HIV, she uses social media to raise awareness. Parker also has appeared in No Shame About Being HIV Positive, a grassroots campaign. Although she is dating a man who accepts her serostatus, she has experienced rejection because of it. She sums it up: “It hurts.”

“Stigma has changed only slightly,” says advocate, blogger and motivational speaker Maria Mejia from Miami. Positive for 25 years, she seroconverted when she was 16. At first, she would tell people it was lupus or leukemia instead of facing the HIV stigma. “I’m also a uterine cancer survivor diagnosed in 2003, but there is a difference,” she says. “If you tell someone ‘I have cancer’ you are more likely to get compassion.”

Later this year, a PWN-USA campaign will tackle HIV stigma directed at women. “It will seek to reframe the narrative on HIV and intersectional issues in the media by engaging women with HIV and allies,” says Olivia Ford, communications director of PWN-USA. “The goal is to produce community-driven messaging, resources and tools, cultivate creative partnerships with media outlets and target key media makers.” Determining how bad stigma is today isn’t just of interest for individuals with HIV, but also for public health. “Stigma is a major factor to accessing HIV treatment, but it must be quantified to develop a stronger response,” says Laurel D. Sprague, research director of the Sero Project.

Determining how bad stigma is today isn’t just of interest for individuals with HIV, but also for public health. “Stigma is a major factor to accessing HIV treatment, but it must be quantified to develop a stronger response,” says Laurel D. Sprague, research director of the Sero Project.

As a result, the U.S. People Living with HIV (PLHIV) Caucus is implementing a nationwide questionnaire on stigma. The U.S. PLHIV Stigma Index is the domestic version of the global PLHIV Stigma Index, which has been completed by people living with the virus in more than 50 countries.

The U.S. survey, which began its rollout this past March, quantifies levels of stigma. It also seeks to quantify stigma within the community with questions such as “Have you been discriminated against by other people who are HIV positive?” As Sprague notes: “If we can’t support each other as a community, how do we come together for any kind of collective action?”

Additional surveys have shown stigma remains a significant barrier to care and treatment. A 2009 Lambda Legal study shows that 63 percent of HIV-positive LGBT people experienced discrimination from health care professionals. Other times, the stigma keeps people from even seeking medical care.

“Let’s say you’re a black gay man living in a community of lower socioeconomic status,” says Terrance Moore, director of health policy at the National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD). “You could be very concerned that someone is going to see you walk into an HIV testing facility, so you may not access that test.” Similarly, you might not want to be seen taking meds, so you skip doses—which can increase your viral load and the risk of transmitting HIV.

These health issues aren’t confined to HIV stigma. NASTAD with support from the MAC AIDS Fund is quantifying stigma faced by black and Latino gay and bisexual men in public health practices. The data suggests that health centers in the South and Midwest convey “high levels” of stigma. As Moore points out, these regions are also likely to be against gay marriage and the expansion of Medicaid benefits. “All of these things are a factor when a person seeks treatment.” What can you do in the fight against HIV stigma? Most advocates would probably agree there is no magic bullet. However, there are smaller steps that individuals can take to help combat stigma. Talking one-to-one with people in your life about the virus is a great place to start.

What can you do in the fight against HIV stigma? Most advocates would probably agree there is no magic bullet. However, there are smaller steps that individuals can take to help combat stigma. Talking one-to-one with people in your life about the virus is a great place to start.

Although some advocates have their doubts about the effectiveness of awareness campaigns, grassroots networks still have faith. Participating in these campaigns, by putting your face in a public service announcement or just by sharing the campaigns on social media, is something we all can at least consider. While the CDC campaigns often recruit from the community, the grassroots campaigns definitely depend on community support. New stigma campaigns seem to be born every day, but here is a sampling of some recent efforts.

HIV Equal was launched in 2013 by World Health Clinicians, an international group based in Connecticut and Zimbabwe. The campaign was created by Project Runway star Jack Mackenroth with celebrity photographer Thomas Evans. Volunteers are photographed wearing an “HIV=” sticker. Their tagline: “Everyone has an HIV status. We’re all HIV equal.”

Also in 2013, Kevin Maloney, a social media consultant and digital activist, launched the No Shame campaign, which features not only Byanca Parker but more than 500 people on Facebook. He launched his first campaign, Rise Up to HIV, after he was diagnosed with HIV in 2010.

The Stigma Project was launched in 2012 by friends Chris Richey, a marketing executive diagnosed with HIV in 2010, and Scott McPherson, the HIV-negative creative director at Here Media, which publishes LGBT magazines such as Out, The Advocate and HIV Plus. The Stigma Project creates graphics that deliver HIV messaging to younger people for sharing on social media. Their logo—a plus and minus sign together—embodies their slogan: HIV neutral.

Whether you join a campaign or start one of your own, getting the word out about HIV/AIDS is key. “We need to be able to share information and awareness,” says Duane Cramer, an HIV-positive photographer who has worked on the Greater Than AIDS and Testing Makes Us Stronger campaigns. “It normalizes the conversation.”

2 Comments

2 Comments