In the mid-2000s, legendary actress and AIDS activist Elizabeth Taylor began hanging out at the elegant West Hollywood gay bar The Abbey, often with her dog, Daisy, in her lap. Staffers and fans wheeled Taylor about in her wheelchair, eager to dote over the woman who almost single-handedly galvanized Hollywood’s response to HIV and AIDS in the mid-1980s.

At the time, many stars would have nothing to do with the disease. But Taylor was not just any star. In 1985, she hosted the first celebrity AIDS benefit, the Commitment to Life dinner, which raised $1.3 million for AIDS Project Los Angeles. Along with Mathilde Krim, PhD, and others, she cofounded the American Foundation for AIDS Research (today known as amfAR). In 1986, she testified before the Senate, demanding more funding for AIDS research. More intimately, Taylor—glamorous in full hair, makeup and jewels—would visit AIDS hospital wards and hospices in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Taylor was particularly upset that gay men were among those hardest hit by the epidemic, since for decades she’d counted so many of them as friends—including Rock Hudson, whose world-shaking 1985 AIDS death played a large role in her activism. “If it weren’t for homosexuals, there would be no culture,” Taylor said at the time. “The idea that God should choose his children [to suffer]—his geniuses to whom he had given the talent to make it a different, more beautiful place for us mere mortals—made me so angry.

In a 1987 speech, Taylor explained why she’d become an AIDS activist in the first place: “I became so incensed and personally frustrated at the rejection I was receiving by just trying to get people’s attention. I was made so aware of the silence, this huge, loud silence regarding AIDS, how no one wanted to talk about it and no one wanted to become involved. Certainly no one wanted to give money or support, and it so angered me that I finally thought to myself, Bitch, do something yourself. Instead of sitting there getting angry. Do something."

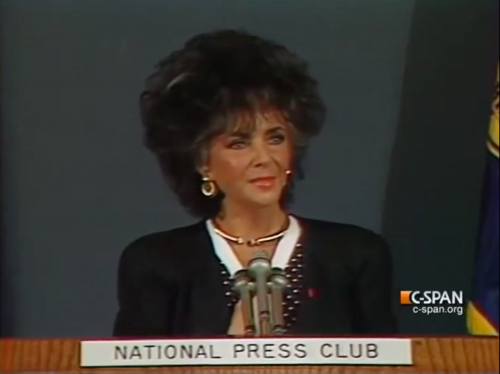

In 1987, Elizabeth Taylor speaks to the National Press Club about the challenge of gaining support and traction for her earliest efforts in the fight against AIDS and how it led her to founding The Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation.

And for years to follow, she did. By the 2000s, thanks in part to her early efforts, powerful new medications had transformed HIV diagnosis from a near-certain death sentence to a chronic manageable illness. In those years, diagnosed with congestive heart failure and holed up in her mansion, attended by nurses around the clock, Taylor almost entirely disappeared from public view. (Here is one of her last public appearances, in 2010.) But among her favorite destinations when she did venture out was The Abbey, where she eventually switched from alcohol to tea, sitting by a portrait she’d donated of herself with her arms outstretched like a saint. She preferred to stop by around dusk, before the popular venue became too packed. In a Vanity Fair article shortly after her death, Sam Kashner wrote:

Even wheelchair-bound, she managed to table-hop. “She’d take her straw out of her watermelon martini and stick it in your drink, and in that flirty little-girl voice she still had, she’d say, What’s that you’re drinking? May I taste that?’” Cooley remembers. “Or she’d say, You’re so handsome—come sit with us.’ And she’d ask personal questions. She’d ask if you were seeing anyone, if you had any love in your life.

Immediately after she died, the bar’s so-called Elizabeth Taylor Room, where her portrait hung, became a shrine, visited by bar patrons bearing flowers (her favorites were gardenias and lilies of the valley), candles, photos of her and a napkin she’d autographed for a fan. According to the New York Times’ visit to the bar after her death:

Sitting untouched on an empty table nearby was a remembrance from the bar staff, a Blue Velvet martini, a bluish drink made with vodka and blueberry schnapps and named in a nod to Ms. Taylor’s 1944 film National Velvet.

“People have been walking up and starting to cry,” said patron Brian Rosman, an Abbey spokesman. “Others can’t talk, they get so emotional.

Taylor was buried in the Jewish tradition—she’d converted to the faith in her 20s before marrying her fourth husband, singer Eddie Fisher—in an LA cemetery where several stars are interred, including Taylor’s good friend Michael Jackson, who’d died in 2009. Her funeral was intimate, attended by only about 40 friends and family members, but it was followed by a large public memorial on the Warner Bros. lot hosted by her good friend actor Colin Farrell. The memorial concluded with Sir Elton John singing “Blue Eyes.” (Taylor was famed for her blue eyes, which often appeared to be violet.)

“To say the world got smaller, emptier, darker and lonelier when we lost Elizabeth is an understatement,” Sir Elton John told the crowd.

Elizabeth Taylor and Elton JohnCourtesy of ETAF/Herb Ritts

Today, the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, which Taylor founded in 1991, is still going strong. In the years since her death, it has supported the large HIV-lobbying event AIDSWatch, funded mobile medical units in Malawi and prominently joined the HIV Is Not a Crime campaign, which aims to raise awareness about outdated HIV criminalization laws across the country.

A new docuseries about her life with the working title, Elizabeth Taylor: Rebel Superstar, has been commissioned by the BBC and is being executive produced by Kim Kardashian.

Following Taylor’s death, AIDS Healthcare Foundation commissioned billboards in her honor around Los Angeles that read: “Our Champion: Elizabeth Taylor.” The Abbey’s founder, David Cooley, told the New York Times that the fact that Taylor spent so much time at the bar in her final years reflected that “she loved us as much as we loved her.”

For more on Elizabeth Taylor, read our interview with her from the November 1997 issue, or click #Elizabeth Taylor to learn more about her advocacy work and the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation.

1 Comment

1 Comment