It’s hard to overstate just how deeply, well, weird POZ seemed when it debuted in 1994. A glossy, glamorous, well-written and beautifully designed magazine…about people with HIV/AIDS?

Though public sentiment on the disease had softened a lot by 1994—with the emergence of the film Philadelphia, of the openly gay and HIV-positive heartthrob Pedro Zamora on MTV’s The Real World, and the ubiquity of the red AIDS ribbon at the Oscars and everywhere else—most people still thought of folks with HIV/AIDS as sad victims, hobbling toward a certain death.

Then suddenly here was a magazine that not only showed HIV-positive people being funny, sarcastic, glamorous, sexy, angry and purposeful, but also talked about HIV treatments (pharmaceutical and otherwise) as casually as, say, Cosmopolitan advised women on how to have a better orgasm.

The public reaction was, to say the least, rather astonishing. As POZ founder Sean Strub recounts in his recently published memoir Body Counts: “Frank Rich, in his New York Times column, said POZ was ‘easily as plush as Vanity Fair’ and ‘against all odds, the only new magazine of the year that leaves me looking forward to the next issue.’” Not a bad note to start on, eh?

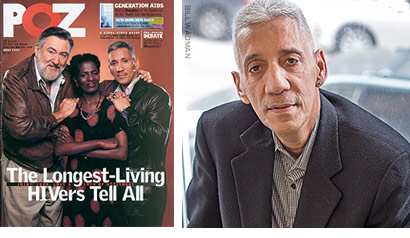

Since then, and over nearly 200 covers, POZ did something else: We charted the byways of the epidemic as it wended its way through the various (and often vulnerable and oppressed) communities affected by HIV/AIDS in the United States and around the world: gay and bisexual men, intravenous drug users, people with hemophilia, sex workers, African Americans and other people of color, prisoners, transgender people, etc. These individuals and communities were not only HIV’s targets but also its fiercest fighters.

The faces that have honored our covers help chart a map of the epidemic as it has evolved over the past 20 years, from a terror with few viable treatment options and a near-certain death sentence attached, to something survivable for people in parts of the world with access to treatment and care, to something that stubbornly will not go away—especially in particularly susceptible communities, such as gay and bisexual men of color. We now have many tools to halt both AIDS-related deaths and new HIV cases worldwide. The question remains: Will we effectively use these tools to eradicate HIV?

Until then, POZ will continue to cover the HIV epidemic until hopefully we achieve our own obsolescence. On our 20th anniversary, we take a look back at 20 of the extraordinary HIV-positive people from many different walks of life, who lit a pathway toward survival, inspiration and even joy for POZ readers. We salute them and the many others who have graced our covers (including those we lost too soon). And here’s to you, our POZ readers. Your stories continue to reflect the diverse tales of the epidemic. June/July 1994

June/July 1994

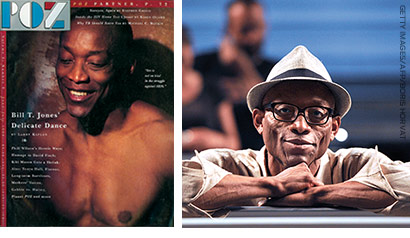

Bill T. Jones

“You know, there must be so many people in the dance world who are HIV positive, yet so few of them have come forward and talked about it publicly, openly.… Oftentimes I am uncomfortable being so alone.”

So began an interview with the legendary New York–based choreographer Bill T. Jones, our second cover subject, six years after his lover and dance partner Arnie Zane had died of AIDS-related complications and the same year he would receive acclaim (and some critical derision) for his landmark Still/Here performance piece on living with chronic illness.

Twenty years later, Jones, 62, is in good health and has since won Tony Awards for his choreographic work for Spring Awakening and Fela! Today, he doesn’t feel so alone as a gay black man living with HIV. “That’s not the first thing a writer says about me anymore, and I really appreciate that,” he says.

Today, when he’s not running New York Live Arts, the nonprofit he merged with his own dance company in 2010, he’s creating a new dance piece, Analogy, due to premiere in June 2015, and he’s got at least another Broadway-friendly project in the making.

He lives in the Hudson Valley with his longtime partner, the French sculptor Bjorn Amelan. “It dismays me that I still meet young men of color who’ve just seroconverted,” he says. “All I can do is embrace them and tell them, ‘Enough with regrets and beating yourself up. Now stay well and do something proactive, because you’re not defined by your illness.’” October/November 1994

October/November 1994

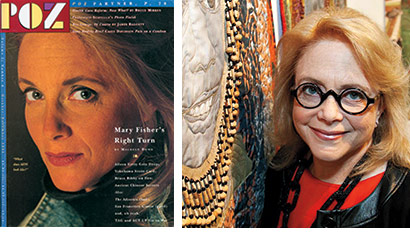

Mary Fisher

The rich, blond-coiffed daughter of a major conservative fundraiser, as well as a wife and mother, Mary Fisher shocked and moved an otherwise reactionary 1992 Republican National Committee crowd when she disclosed her HIV-positive status at the podium, entreating Republicans to provide more compassion—and funding—for the then-raging epidemic.

“Though I am female and contracted this disease in marriage, and enjoy the warm support of my family, I am one with the lonely gay man sheltering a flickering candle from the cold wind of his family’s rejection,” she told the crowd. “People with AIDS have not entered some alien state of being. They are human. They have not earned cruelty, and they do not deserve meanness.”

Two years later, New York Times writer Maureen Dowd visited Fisher’s sprawling suburban home outside Washington, DC, for POZ, finding a gracious woman who’d started a national AIDS support group, published a memoir and crisscrossed the country speaking to schools about HIV/AIDS.

Today, having survived not only decades of HIV but also breast cancer, Fisher, 66, lives in Sedona, Arizona, where she makes art and contributes to causes, such as “100 Good Deeds,” to help poor women around the world. (Read more about her work at maryfisher.com.) “I plan to live long and well, trying to make a difference and remembering that if I care for others, I’ll never need worry,” she said. “Everything else will take care of itself.” December 1994//January 1995

December 1994//January 1995

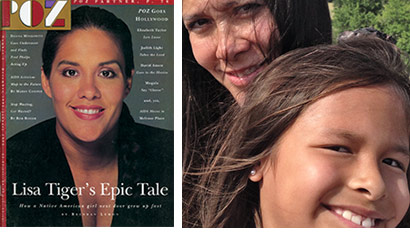

Lisa Tiger

In her moving cover story, Lisa Tiger, then 29, talked about growing up Cherokee Indian in Oklahoma, dropping out of college in 1992 when she learned she was HIV positive and being tapped by Cherokee leader Wilma Mankiller to become a national speaker on HIV prevention and overall wellness among American Indians—a community that has high rates of substance use.

“People listen to me because I’m a Native American when they wouldn’t listen to the same story from a white woman,” she told POZ. Twenty years later, Tiger now lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico, with her beloved 9-year-old daughter, Taladu, whose name means “cricket” in Cherokee. She’s still close with Taladu’s dad, her ex-husband, who lives nearby and helps raise their daughter.

She’s back in school finishing her bachelor’s degree in film, and though her HIV is in check, she’s fought Parkinson’s disease the past 15 years. In addition, her adopted daughter, Shelleigh, was murdered by her boyfriend in 2007, on the same day Tiger’s father was murdered 40 years before.

“Life has humbled me since that article in POZ,” she says. “I’m broken, but I’m kinder. Back then, I couldn’t forgive the guy who gave me HIV without telling me he had it.” She says she’s since forgiven him, as well as many others. “You have to let go of resentments,” she says. “It’s better for you.” April/May 1995

April/May 1995

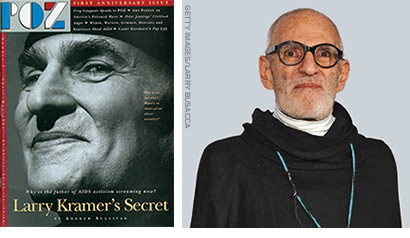

Larry Kramer

In 1995—14 years after he co-founded GMHC, 10 years after he debuted his searing AIDS stage drama The Normal Heart, and eight years after he sparked the transformative activist group ACT UP with a single enraged speech—Larry Kramer graced the cover of POZ.

It was a crackling conversation with his fellow HIV-positive luminary Andrew Sullivan about AIDS activism in the era of President Bill Clinton, complacency about HIV among gay people, the pros and cons of the early AIDS drug AZT, and even the existence of an afterlife.

“I certainly think Donna Shalala is evil,” Kramer then said of Clinton’s health czar, whom he accused along with Clinton of doing too little on AIDS. “Evil, evil, evil.” The fiery godfather of activism has appeared on our cover three other times (in 1997, 1999 and 2007) and famously received a new liver in 2001 to replace one ravaged by hepatitis B.

Today, Kramer lives in Connecticut with architect David Webster, his partner of 20 years whom he married in the I.C.U. while recovering from surgery last July. Director Ryan Murphy’s HBO adaptation of The Normal Heart, starring Mark Ruffalo and Julia Roberts, debuted in May. The American People, a giant historical novel Kramer has been working on for years, will come out later this year, according to a colleague of Webster’s.

Kramer, 78, is currently in poor health and was unable to chat with us for this follow-up. But when we saw Kramer at an ACT UP reunion in New York last summer, he was asked what he wanted to say to those assembled, whom he called “my children.” He simply answered, “I love you.” June/July 1996

June/July 1996

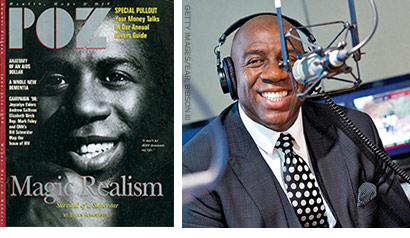

Magic Johnson

“Larry Kramer has been very effective as an activist and has done many wonderful things for people with HIV and AIDS. But I decide what my role will be, not anyone else.” So said 36-year-old LA Lakers legend Magic Johnson in 1996, who’d returned to his basketball team for a final stint on the court, when POZ told him that Kramer and other HIV activists were dismayed he’d not done more to fight the epidemic since his history-making 1991 announcement of having HIV.

After retiring as an NBA player, Johnson, 54, has become a super-savvy multimillion-dollar entrepreneur, investing in everything from movie theaters and Starbucks in low-income urban areas to, just a few months ago, the WNBA’s LA Sparks team. But he also has continued his advocacy and has raised money for HIV/AIDS causes via his Magic Johnson Foundation.

He also hasn’t shied away from clearing up HIV myths in the black community, such as that he was “cured” of HIV or that he remained healthy through exotic foreign treatments, as opposed to standard HIV meds. Today, Johnson is still advocating the benefits of antiretroviral therapy and the need for individualized treatment. “The virus acts different in every body,” he said on a recent radio show. “Just because I’m doing well, you might not do well.”

In other news, he and his wife Cookie have shown public love and support for E.J., their 21-year-old gay son, a New York University student and emerging fashionista. December 1996/January 1997

December 1996/January 1997

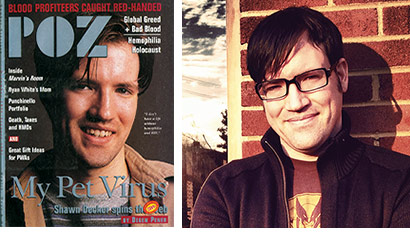

Shawn Decker

The year 1997 was a big one for longtime POZ columnist and blogger Shawn Decker. Born with hemophilia and diagnosed with HIV (which he got through infected clotting factor) in 1987 when he was 11, Decker experienced an otherwise normal Virginia boyhood—although one that had been cloaked in HIV secrecy.

But in 1997, he started his My Pet Virus website, a humorous, goofy and educational online chronicle of his young suburban hetero life with HIV. Soon enough, he was writing a regular column for POZ called “Positoid,” which made him one of the nation’s funniest openly HIV-positive people. Seventeen years later, Decker, 38 and still a Virginian, is doing great.

In 2000, he married Gwenn Barringer, a fellow HIV-negative AIDS educator, and the two have run a sero-diverse HIV education road show ever since, blogging jointly at shawnandgwenn.com. In 2006, the couple appeared on our cover together when he published his memoir version of My Pet Virus, which he is now turning into a screenplay.

The couple, who just last year graced our cover again for our “Negative” special issue, has two nieces and a goddaughter they adore. “I want to maintain and improve my health as I head into my 40s,” Decker says. “I want to be in the best shape possible when cures for both HIV and hemophilia come down the pipeline so I can really enjoy my final years.” October 1997

October 1997

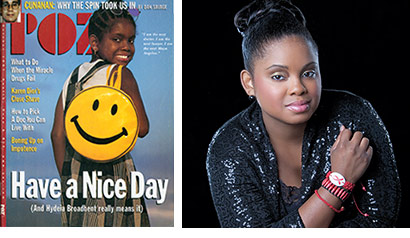

Hydeia Broadbent

One of POZ’s sunniest covers featured 13-year-old Hydeia Broadbent, who’d become a media sensation as the little girl born with HIV and adopted by parents in Las Vegas. By 1997, she’d survived several near-death illnesses, was in good health on one of the new HIV combos and was crisscrossing the nation as a sassy, singing-and-dancing, one-woman HIV education tour de force. (She was even on Oprah.)

Seventeen years later, Broadbent, who celebrates her 30th birthday in June, has gone on with her own show. Still based in Vegas, where she lives with her HIV-positive sister, Patricia, she continues to travel and speak before audiences on the modern-day realities of HIV, and she’s a spokesperson for the “Until There’s a Cure” campaign.

Not that she didn’t need to take some time out of the spotlight: “The public turned me into a celebrity, which at times was too much to bear,” she confides today. “The time came when I had to figure out who Hydeia was.”

Eventually she was ready to return to the public eye; recently she reconnected with Oprah to discuss the challenges of dating with HIV (a guy she liked was too ashamed to be seen with her) and her dreams of starting her own nonprofit and community center. “I have a lot of plans, too many to name,” she tells us. “So just keep an eye out for your girl.” You can do just that at hydeiabroadbent.com. February 1998

February 1998

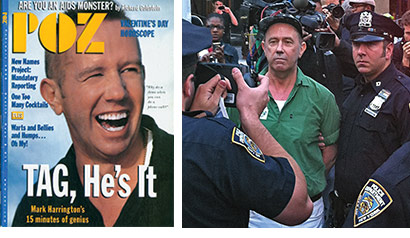

Mark Harrington

“Why do a demo when you can do a phone call?” That’s what New Yorker and HIV-positive treatment activist Mark Harrington told POZ in 1998, explaining why he and a few other scientifically minded colleagues had broken away from the street-fighting ACT UP and started their own elite research club, Treatment Action Group (TAG). The new group redesigned HIV drug trials alongside honchos from the Clinton administration and earned Harrington in 1997 a $240,000 MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant.

At that time, the AIDS death rate in the United States had just plunged by 67 percent because of the new protease inhibitors—“it was a period of great excitement,” he recalls today—even as ever more patients were developing resistance to them. Shortly after that, Harrington would expand his work to address the growing global AIDS pandemic, which was interacting with such diseases as tuberculosis and malaria.

Fifteen years later, TAG is still going strong, focusing on matters local (teaming up with a newly resurgent ACT UP New York to demand an end to AIDS in the state), national (scaling up use of pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP) and global (making sure that the forthcoming all-oral hepatitis C drugs are available worldwide, as well as expanding access to treatment for tuberculosis).

Harrington, 54, demurs talking about his personal life. “Trying to find a life-work balance has always been a complex issue,” he says. But he freely admits, “I’ve been blessed with a healthy family, wonderful friends, brilliant colleagues, good health and challenging work.” April 1998

April 1998

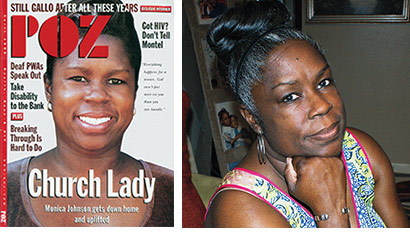

Monica Johnson

When POZ visited Monica Johnson in rural Columbia, Louisiana, she’d already been through a lot—HIV positive since 1985, still mourning the 1993 death of her beloved baby boy Vaurice, who’d been born with HIV, and dealing with local AIDSphobia so severe that she was pulled off her substitute-teaching position and relegated to a back office. But to her joy, she also was undetectable on combo therapy and happily raising her sister’s son, Avery.

“People were so ignorant,” she recalls. “You couldn’t talk about HIV/AIDS publicly anywhere.” Johnson moved that needle when she founded her own AIDS agency, HEROES, which she still runs today, though she laments that budget cuts have weakened it. She’s also served on the National Minority AIDS Council board of directors and has been featured in the acclaimed documentary deepsouth, about the paucity of HIV resources and funding in states like Louisiana.

“Sometimes I feel as if I live in a developing country when I compare the services in other parts of the United States to what we have in Louisiana,” says Johnson, 49. That’s why she’s sticking with HIV advocacy even though she’s suffered burnout. “After prayer and reflection, I decided I couldn’t abandon it.”

A point of joy? She recently watched Avery graduate high school and go on to college. Now she’s ready to write a memoir—and to start running marathons! “My faith has held me together,” she says. February 1999

February 1999

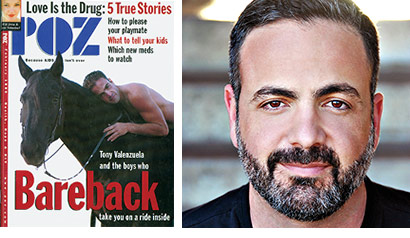

Tony Valenzuela

Perhaps POZ’s most sensational and controversial cover featured the young, HIV-positive gay activist, sex worker and porn star Tony Valenzuela naked astride a saddle-free horse, two years after he’d confessed before a crowd at a San Diego LGBT political conference that he cherished condomless sex.

“The level of erotic charge and intimacy I feel when a man comes inside me is transformational,” he’d said, stressing he was speaking only for himself, not advocating barebacking for all. Nonetheless, the room exploded with angry declarations that Valenzuela was setting back the safer-sex movement. The blowback blacklisted him in San Diego, so he moved to Los Angeles, where he got his MFA in creative writing and became the head of the Lambda Literary Foundation, an LGBT writer’s organization.

“A lot of HIV clinics wouldn’t carry that month’s issue of POZ,” he recalls. “But that cover also served as a turning point. The topic of barebacking was out in the open, and we created some space for gay men to speak honestly about their desires.” Valenzuela, 45, still lives in Los Angeles with husband Rob Ferrante and their two pit bulls, Scarlett and Chauncey. He’s working on a memoir about his barebacking brouhaha.

“A lot has improved for us” since the late ’90s, he says. “But I also think HIV-positive gay men have no agency. Our lives tend to be demonized or framed as victims in media and by public health. We still need to assert our stories on our terms, our bodies on our terms.” March 1999

March 1999

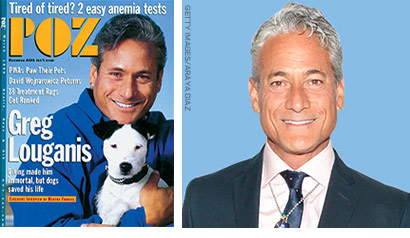

Greg Louganis

When POZ caught up with Olympic diving legend Greg Louganis at his Malibu home in 1999, it was 11 years after he shockingly slammed his head on the diving board at the 1988 Olympics and five years after he released Breaking the Surface, his bestselling memoir in which he came out as both gay and as HIV positive.

He was no longer in the Olympic mix, but his health was holding steady on protease inhibitors and he’d found a new passion—raising dogs, such as his Jack Russell terrier, Nipper, who posed with him on the cover.

Fifteen years later, Louganis, 54, is still as active as ever, having hosted Splash, a celebrity diving reality show, and, last fall, having married handsome paralegal Johnny Chaillot in a Malibu wedding attended by celebs like Barbara Eden and fellow Olympian Nadia Comaneci. He still loves dogs—his latest is Dobby, Nipper’s son. He says he’s been lucky to live all these years with HIV.

“When I talk to colleges and young people about HIV prevention, I tell them we’re in a different day and age now,” he says, “but that if they can avoid HIV, they’re better off. I’ve been positive for 26 years now, I’ve been on nearly every med, and I wouldn’t wish my drug regimen on anyone.” June 2001

June 2001

Ruben Rodriguez

New Yorker Ruben Rodriguez, diagnosed with HIV in 1994 but likely positive years before that, was already a longtime survivor when he shared the cover of POZ with Anthony Salandra and Marsha Burnett, two other HIV veterans who’ve both since died.

That summer before 9/11, he was working as the hotline supervisor at the Osborne Foundation’s AIDS in Prison Project, after himself being paroled in 1996 after 15 years in state prisons, where he not only kicked drugs but also started groundbreaking programs for HIV-positive prisoners. “People aren’t nearly as afraid of AIDS as when we started,” he told POZ back then. “Prisoners coming together to help each other forged a sense of community.”

Thirteen years after his POZ cover, Rodriguez, 63, is working as a life skills coordinator at New York’s Fortune Society, which helps parolees re-enter society. “I still live with my significant other, my T cells are at about 440, I’m undetectable, and life continues to move along,” he reports. He loves his job. He’s also a cancer survivor.

“Look,” he says with his characteristic Brooklyn no-B.S. style, “I’ve survived more than 25 years in and out of prison, drug addiction, HIV/AIDS, lymphoma, prostate cancer, living with hepatitis C, and all that life has thrown at me. I’m a blessed man.” November 2008

November 2008

Waheedah Shabazz-El

When fierce Philadelphian Waheedah Shabazz-El appeared on POZ’s cover, four years had passed since she learned she was HIV positive while serving a six-month stint in prison for a drug bust.

After that stint, in addition to getting clean from drugs, this proud progressive Muslim grandma took up advocacy for HIV-positive prisoners with a vengeance, working with the Philly activist group Philadelphia FIGHT, where she is employed today, and becoming a founding member of the national Positive Women’s Network USA, for which she is now regional organizing coordinator.

She also played a major role in re-legalizing condoms in Philly jails. “I realize that I have been reborn and re-created again and again,” she says today. Currently on her agenda? Fighting laws that criminalize HIV-positive people for having sex, even when their virus is undetectable and virtually untransmissible. “Those laws undermine an environment where people will come forward to be tested and treated,” she says.

Otherwise, post-prison life for Shabazz-El is sunny. “I’m happy, secure and in a healthy marriage with a wonderful man who’s also an activist. We recently purchased a home, and I enjoy being a sexy wife and grandmother as much as I enjoy being a public figure in the community.” December 2008

December 2008

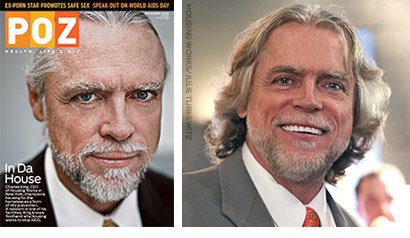

Charles King

Just over a year after appearing on the cover for our feature story showing that stable housing reduces both HIV rates and HIV-related illness, Charles King, the HIV-positive co-founder of Housing Works, cut off his signature ponytail in an event that raised $15,000 for relief in Haiti after its devastating 2010 earthquake.

Since the demise of his long locks, King, 59, has been busy as usual, both globally (after Haiti’s earthquake, Housing Works opened a small office there to help fight the country’s poverty and its AIDS crisis) and locally (the agency is working closely alongside New York officials and other activists to help bring both AIDS deaths and new HIV cases to zero in the state by 2020).

A recent victory occurred when New York City finally capped rent for poor folks living with HIV at 30 percent of their income—something Housing Works had long been agitating for. On the personal front, King also is an adoptive daddy of sorts now, helping to raise two teenage boys, with another one—the son of Jobanny Ramirez, King’s Dominican partner of seven years—likely on the way into his household.

“I have to cook a lot on the weekends, so there’s always food in the fridge,” he says. But he continues to keep his eyes on the fight. “With the advent of [post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and treatment as prevention (TasP)], it is clear that we can end the epidemic,” King says. “We need to be demanding this more loudly than ever.” January/February 2010

January/February 2010

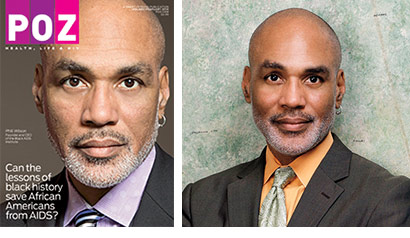

Phill Wilson

Phill Wilson has lived with HIV since 1980, and in 1999 he founded the Black AIDS Institute in Los Angeles to fight the epidemic among African Americans. Shortly before he appeared on POZ’s cover, he played a key role in launching Greater Than AIDS, a social media campaign to empower the black community to unite and fight the disease.

“My first priority…is to develop messages that resonate with black folks,” he told POZ. “When 50 percent of all new HIV cases in this country are in black communities, when 50 percent of the 1.1 million people estimated to be living with HIV in America are black and when 50 percent of all AIDS-related deaths in the United States are black, I don’t think there’s any room to debate that AIDS in America is a black disease.”

Since then, not surprisingly, Wilson, 57, has been busy. He had a hand in making sure that the XIX International AIDS Conference in Washington, DC, in 2012 included “an unprecedented number of black keynote speakers,” he notes, and the Black AIDS Institute has been a major force in urging blacks to sign up for Obamacare by stressing that health care coverage helps people prevent, diagnose and treat HIV.

His goals going forward? “To meet the promise of achieving an AIDS-free generation,” he says. “My goal is to proudly be able to close the doors of the Black AIDS Institute because our job will be done.” June 2011

June 2011

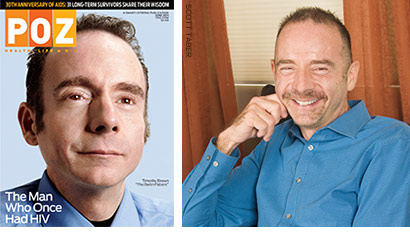

Timothy Ray Brown

When POZ chatted with Timothy Ray Brown for our cover story, five years had passed since German doctors had famously managed to cure his HIV by reinfusing him with immune cells that have an HIV-resisting mutation, which was part of his successful treatment for leukemia. Brown, a gay American who had been living with HIV in Berlin for a decade before his 2006 leukemia diagnosis, became a one-man proof of the concept that HIV could be cured if pre-existing virus could be scoured from the body and if the immune system could also be programmed to block new HIV from replicating.

“It’s really great,” said the mild-mannered Brown. “I hope what I’ve gone through will help lots of people.” Three years later, even as new scientific challenges to a cure have emerged, Brown himself is doing well, living between San Francisco and Las Vegas with his new boyfriend, working again as a German-English translator and putting muscle back on at the gym. He remains free of both HIV and leukemia.

He also started, in 2012, the Timothy Ray Brown Foundation, to promote cure research. And last June in his hometown of Seattle, he launched “The Cure Tour” with the Fred Hutch Cancer Research Center. “I visit cities around the world and host a cure scientific symposium,” he explains. “The goal is to spread the word that a cure is possible, and to gain global support to fund cure research around the world.”

When he’s not advocating for a cure, he stays busy doing Tuesday-night movie dates with his boyfriend and sticking to a vegetarian diet, “which when I have the urge to eat fast food is really hard.” September 2011

September 2011

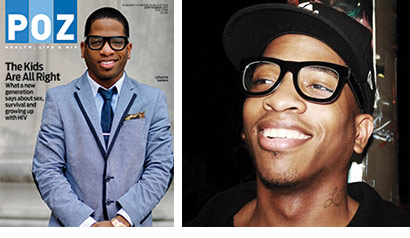

Lafayette Sanders

In our feature story on young people who were either born with HIV or got it in their teens or early 20s, Philadelphian Lafayette Sanders, then 24, told the story of losing his mom to HIV at 13, keeping his own perinatally infected status a secret for years at his grandma’s urging, suffering stress and rage, then finally finding solace when he came out with his status publicly and became a sexual-health advocate for young people.

Three years later, Sanders is still advocating. A teen sexual-health video documentary he took part in landed him a spot touring with BET’s Rap-Up tour. Living with his girlfriend, he does visual merchandising at J. Crew while working on his own fashion line, Kustoms By L.K.

He’s got big personal plans for the future: “to remain happy and healthy, to take care of my family, to get engaged, travel, get married, have healthy kids.” But he’s also committed to ending the epidemic. “We still have plenty of work to get done,” he says. “Information still isn’t reaching the young on an efficient scale. I want to break the cycle of my parents and break down the walls of stigma attached to HIV. If someone really gives me the platform,” he promises, “I’ll change it!” September 2012

September 2012

Cecilia Chung

“The change for me from being male to coming to my womanhood was a very painful journey,” HIV-positive transgender San Franciscan Cecilia Chung told POZ in our feature story on research linking trauma and HIV among women and transgender women, and on programs to help them heal wounds from their past.

Chung recounted being rejected by her family and losing her job as a court interpreter when she transitioned to womanhood in the ’90s, and how those blows led to her using drugs and becoming HIV positive. That’s all behind her now.

Today, Chung, 48, is one of San Francisco’s seven volunteer health commissioners and is also a senior strategist at the city’s Transgender Law Center. She helped implement an HIV testing program for area transgender youth, plus she was elected president of the U.S. People Living with HIV Caucus and named by President Obama to the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS.

“I like to keep busy,” jokes Chung, who in her downtime likes to get foot massages with her boyfriend. Mostly, though, she’s passionate about creating a national network of HIV-positive transgender women. “It’s time for that,” she says. “Our voices are still kind of invisible, so we need to get more trans women with HIV to step into the advocacy role.” April/May 2013

April/May 2013

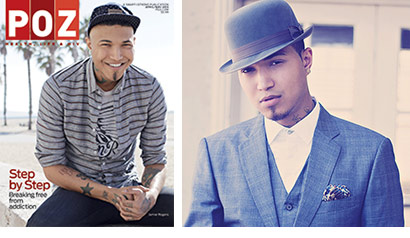

Jamar Rogers

“I was able to speak my truth with no shame.” That’s how Jamar Rogers remembers feeling about being on POZ’s cover last year linked to a story on HIV-positive people fighting addiction. Rogers had already spoken his truth the year before, when, as a contestant on the hit singing show The Voice, he’d come out as HIV positive and a recovering crystal meth addict.

He parlayed the fame not only into his singing career, but also into the speaking circuit, sharing his empowering comeback story. A year later, Rogers, 32, says he’s staying clean through “a lot of volunteer work with churches, youth groups and HIV organizations.” Last year, he got signed to Tommy Boy records and toured South Africa; he also was sick with tuberculosis for five months. No wonder his next album is called Lazarus.

And guess what else? “I’m engaged to an HIV-negative woman who has decided to love and support me,” he reports. But in addition to wedding plans, he’s still speaking out about HIV. “We still have such a long way to go,” he says. “The black community is still taking the brunt, and I believe it’s because we have no self-identity. If we valued and loved ourselves a little more, maybe we’d get tested regularly. Perhaps we’d actually take a stand for ourselves and our loved ones.” January 2014

January 2014

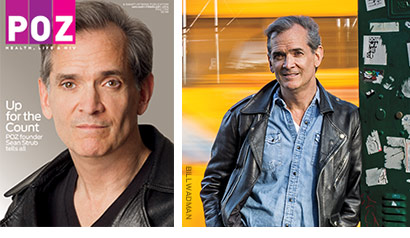

Sean Strub

One of our most recent cover boys also happens to be our magazine’s founder, Sean Strub, an LGBT rights fundraiser and ACT UP alum who was nearly dead from AIDS-related complications in 1994 when he launched POZ. To finance this bold leap of faith, Strub used $345,000 he got from selling his life insurance to a viatical company, one of those pre-protease ventures that bet financially on the impending deaths of people with HIV/AIDS.

“We tried to tell the story of the epidemic in all its complexities, through the experience of those with HIV,” recalls Strub of POZ’s mission. “And we would do so in an attractive, engaging and hopeful format—on glossy paper.”

That quote is from Body Counts, Strub’s recently published memoir of 35 years of being an LGBT and HIV/AIDS activist, which The Washington Post said “has the suspense and horror of Paul Monette’s memoir Borrowed Time and the drama of Kramer’s play The Normal Heart.”

Not surprisingly, Strub, 55, who sold POZ in 2004, has been traveling the country promoting the book and meeting with positive folks in all corners of the United States. He also founded the Sero Project, which fights to repeal laws that criminalize HIV-positive people for having sex, even when they’re undetectable and use condoms and no virus is transmitted.

“It’s moving when people tell me how the book overlaps with their own stories,” he says. “And, of course, I hear from people all the time how much POZ has meant to them, and that makes me very proud.”

3 Comments

3 Comments