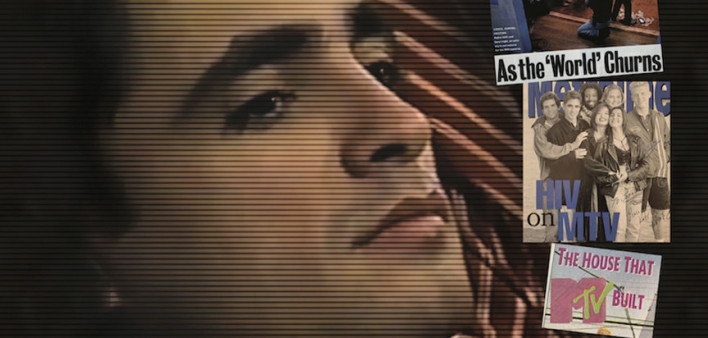

Pedro Zamora was a Cuban-American AIDS educator in Miami when he was cast in the third season of MTV’s reality TV show The Real World: San Francisco, which aired in 1994. One of the first openly gay and HIV-positive people depicted on television, Zamora won over viewers with his charisma, smarts and, yes, movie-star looks. “I thought being on the series would be a great way to show how a young person actually deals with HIV and AIDS,” Zamora told POZ in our third issue, dated August/September 1994.

POZ August/September 1994

While on The Real World, Zamora also showed the world that a gay person with HIV could fall in love and get married. In another groundbreaking cultural moment, the series broadcast the (then-illegal) wedding of Zamora and Sean Sasser, a fellow HIV-positive AIDS educator whom Zamora met at an LGBT march in Washington, DC. Alas, Zamora died of AIDS-related illness just hours after the final episode aired in November. He was 22.

Fast-forward to today. Leo Rocha is a 23-year-old, gay Colombian American who grew up in Texas and now lives in New York City, where he works for Mic (Bustle Digital Group). While earning his journalism degree from the University of Missouri, Rocha was part of a documentary film team that wrote, filmed and edited Keep the Cameras Rolling: The Pedro Zamora Way (Method M Films), which revisits the life and legacy of the iconic figure.

The documentary has been playing the film festival circuit, including a 1 p.m. screening Sunday, October 16, at NewFest, New York’s LGBTQ film festival; as part of the NewFest virtual program, viewers nationwide can watch it October 13 to 25 (visit NewFest.org for more info on how you can stream it at home).

POZ spoke with Rocha, who is one the film’s nine writers, to learn more about his experiences making the movie. Our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You were born five years after the 1994 season of The Real World was broadcast. Did you know about Pedro before joining your university’s film project?

I had not heard about him before. Since I was like 12 or 13, I’ve been very interested in social justice issues and have been adamant about the importance of representation—queer and Latino—so the fact that I had never heard about him was shocking to me. And the fact, too, that this season of the Real World had the first gay marriage on TV—in 1994! I was shocked that this happened—I don’t want to say “so long ago” but that early on. It made me feel like I was robbed of having this inspirational figure to look up to. There wasn’t much queer or Latino representation when I was growing up. We had, like, Glee, which was predominantly white. In terms of Latino representation, there was Ugly Betty and Jane the Virgin. That was pretty much it.

Journalist and writer Leo Rocha worked on the documentary “Keep the Cameras Rolling: The Pedro Zamora Way.”Courtesy of Leo Rocha

How did you first learn about HIV?

Being that I grew up in Texas, I was not taught about it in school at all. Maybe in seventh-grade health class it was like a bullet point on a PowerPoint slide on sexual health. I didn’t really know much. I first heard about it through the internet, maybe in 2008 or 2009. I was like 8 or 9 and frequenting chat rooms—a time when I should not have been allowed on the internet [Laughs]. That’s how I was first exposed to the topic of HIV.

What was the context?

It was very negative, unfortunately. I didn’t know what it meant. After I googled it, I knew it was a virus, but it wasn’t until I was in high school and a little older and got more educated on social justice issues through Tumblr, that I learned the full context and significance of HIV and the horrible impact it has had on the queer community.

When did you come out?

I came out at a very young age to my mom. I was 12. I remember because I wanted her to vote for Obama for his reelection—so it was 2012 or 2011—she was leaning toward voting for Mitt Romney, and I was like, I need to nip this in the bud. My mom was a little taken aback. Like, “Oh you must be confused.” But it never got worse than that. She’s very accepting now and proud of the work I’ve done.

How did you research the film?

We studied the history of HIV in the ’80s and ’90s and the political response to it and the pop culture context. We found episodes of The Real World on some obscure site—someone had taped it on their VCR and uploaded it digitally—but now you can watch them on Paramount+.

The documentary crew interviews former President Bill ClintonCourtesy of Leo Rocha

What surprised you or affected you the most as you worked on the film?

Obviously, that Pedro even existed, and I didn’t know of him. And all that he accomplished, especially the aspect of representation—the importance of a healthy interracial relationship with two people of color. For me, being a person of color, growing up, all I saw was white gay guys and white faces and relationships. You internalize that as a little kid, and I struggled with a lot of self-esteem issues, like “Why do I have this Afro hair?” Maybe if I had learned of Pedro early on and seen him and Sean on TV, hugging and kissing and going on dates, that would have helped me a lot in my journey.

How have audiences responded during the screenings?

Fantastic. The intergenerational aspect has come up at every screening, in terms of there being younger people who never knew about Pedro and then some who grew up watching him. And they’d discuss [the importance] of preserving this history and teaching it to another generation. We’ve also had a lot of people who are either living with HIV or had loved ones die of HIV and who come and watch the movie and have been blown away and are appreciative of what we did. There have been a lot of tears at the screenings.

The poster for the documentaryCourtesy of Method M Films

For the film, you and the team interviewed former Real World castmates, Pedro’s sister and father, former President Bill Clinton and Anthony Fauci, MD, the national health leader. How was that?

I never expected I’d interview a former president. I was 19 at the time. We went to the Clinton Foundation’s Harlem office. It was really cool. It’s funny how in 2018 [when we started the project], we were most excited about interviewing Clinton, but now, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Fauci is more relevant. It’s interesting to me, because I love learning about history and seeing how one thing leads to another. In this massive COVID pandemic and now monkeypox, we’re seeing a lot of connecting threads, like seeing Dr. Fauci in the 1980s spearheading the AIDS response and now spearheading the COVID response. You see history repeating. And not just the connection between AIDS and COVID. But also [gay rights and marriage equality]. There’s the “Don’t Say Gay” law in Florida, and a Texas judge just ruled that [a company’s health insurance plan] doesn’t have to cover HIV prevention medication.

The documentary crew interview Pedro Zamora’s sister Mily.Courtesy of Leo Rocha

And I want to thank the Zamora family. I was the only Latino person and native Spanish speaker on the team, so I was kind of the intermediary. They were incredibly welcoming and supportive. When we went to interview them, his sister Mily had this big Cuban breakfast ready for us and kept feeding us. It was really special to experience that. I made it clear to them how important Pedro’s story was to me and that we’d get it right.

Comments

Comments