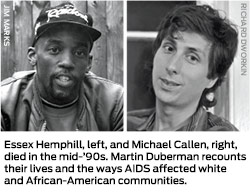

Michael Callen was an outspoken activist and singer living in New York City; Essex Hemphill was a black poet in Washington, DC. They weren’t friends, but both were gay and died at age 38 in the mid-’90s. Why profile them and this period of AIDS history?

Michael Callen was an outspoken activist and singer living in New York City; Essex Hemphill was a black poet in Washington, DC. They weren’t friends, but both were gay and died at age 38 in the mid-’90s. Why profile them and this period of AIDS history?

It’s part of the story that has been least told, the pre-ACT UP story. I think the lives themselves of Mike and Essex needed retrieval. Both were extraordinary men, very brave, very generous in terms of helping others. Mike started his own group, the People With AIDS Coalition, which did an awful lot of good work. Its newsline—I was a volunteer there for a couple of years—was a real lifeline to a lot of people. The phones were constantly ringing from people asking for information. But their work just isn’t as well known as GMHC or ACT UP.

And one of the central themes of the book is the different ways AIDS has impacted the white and African-American communities. The story of how the white gay world in general has treated black gay people has itself not been well told.

Essex was less overt than Mike regarding sexuality and HIV activism. Is that indicative of race or socioeconomic status?

For Essex, “home” was not the gay community, it was the black community. And he didn’t want to lose his ties to it. In general, the unspoken pact [in the black community to gay members] was that, “You belong to us, you remain family, but you do not become publicly or politically active on behalf of your sexual orientation.” Essex brought it up often.

Did Mike also represent a larger social group?

Mike represents a number of people—those who attended the 1983 Denver conference, for example. Very few of their names are remembered, but they did very important work. They established the central principle that PWAs [people with AIDS] are not victims, they are the experts on their own lives and what’s happening to their own bodies. That was one of Mike’s objections to GMHC. Namely, that no PWAs were on the GMHC board. Instead PWAs were supposed to sit in an audience and listen to the so-called experts tell them about their own lives.  Would Mike’s sexual politics raise eyebrows in today’s age of gay marriage?

Would Mike’s sexual politics raise eyebrows in today’s age of gay marriage?

He spoke of having thousands of sexual partners. Mike is a product of the 1970s, the decade of sexual liberation. The gay movement the first years after Stonewall was radical. Mike was not an advocate of assimilation. He thought gay people were valuably different and should use that as a way of educating and changing the mainstream. Mike was a radical in his perspectives, and he never lost that. And that’s precisely what the gay movement, in my opinion, needs today.

ALSO…

It’s no surprise that Michael Callen gets namechecked in Leslie L. Smith’s Sally Field Can Play the Transsexual. As a gay, HIV-positive director-turned-author, Smith weaves current topics—survivor’s guilt, condomless sex and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)—into his serio-comic novel about a gay hustler in New York City who must contend with a dying mother in Arkansas and the recurring ghost of a wealthy mentor who died of AIDS complications.

Past and Present Tense

Historian Martin Duberman, author of Hold Tight Gently, explains why we should never forget AIDS pioneers Michael Callen and Essex Hemphill.

Comments

Comments