After many years of shopping at Housing Works thrift shops and bookstores across New York City, Gavin Browning noticed one day that the nonprofit’s logo included a gay pride triangle as a rooftop. “I wondered, What does that mean? What actually is Housing Works?” he recalls. “So I did some research and found out it was this really interesting group that built housing for homeless people with HIV, and it came out of ACT UP in 1990. There was this amazing history right under my nose!”

Currently the director of public programs and engagement at the Columbia University School of the Arts, Browning has a background in urban planning, publishing and architecture. He was so drawn to the story of Housing Works that he got a Graham Foundation grant to create HousingWorksHistory.com, a digital timeline spanning 1990 to 2015 and including a mind-boggling collection of data and ephemera, such as architectural renderings, T-shirts, details of Housing Works programs, HIV/AIDS rates, city housing policy, court cases, minutes of meetings and videos of speeches—much of which had to be digitized. “I bought one of those TV/VHS combinations on eBay so I could watch bags and bags of old VHS tapes,” Browning said.

One day in 2015, folks brought in their personal collections of Housing Works–branded items, such as T-shirts and posters, so Browning could photograph them for the archive (people then took their stuff back home). All this was necessary, Browning says, because “the activists were busy fulfilling their mission—their priorities, rightly, were building homes, not doing self-promotion—so they didn’t have time to steward their history.”

(continued below)

As Browning delved into Housing Works’ closets and file cabinets, several amazing narratives emerged. “For me, it became a story of how AIDS activists became real estate developers and how a public health crisis was addressed by architecture,” Browning says. “Plus, there’s that idea of housing as health care, that you can’t get healthy without a roof over your head.”

The topics of HIV and homelessness, Browning says, give rise to a lot of emotions, and the research did get intense at times, especially with people sharing intimate stories. “A lot of Housing Works employees were once clients,” he says. “They had really overcome a lot and are success stories, so I wanted this to include as many voices as possible, including people who are no longer here.”

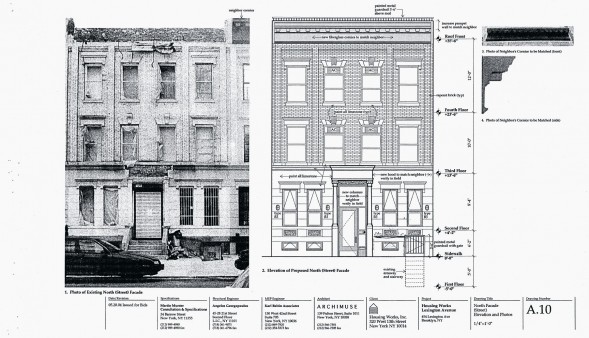

He also wanted the archive to include multiple media formats. To that end, he produced five films, each one focusing on one of the organization’s housing programs: the Keith D. Cylar House Health Center (which was built from the ground up and opened in 1997 in the East Village), the East New York Community Health Center (opened in 1998 and built from the ground up on the former site of a gas station in Brooklyn), the Transgender Transitional Housing Program (a “scattered-site” program started in 2004), the Stand Up Harlem House (a pair of renovated brownstones that opened in 2008) and the Women’s Transitional Housing Program (opened in 2009 for women coming out of prison).

Together, these films offer a fascinating glimpse at how the challenges of homelessness and HIV have been approached throughout the course of the epidemic in New York City. For example, in the 1980s, the city’s attitude was that homeless people with HIV could stay in shelters with the rest of the homeless population. But as Housing Works’ Virginia Shubert explains, tuberculosis was spreading in the shelters, and that was dangerous for people with HIV—they needed their own housing.

When the Keith D. Cylar center opened, it was unusual in that it didn’t feel like a nursing home or shelter. Housing Works hired architect Alan Wanzenberg, whose specialty was residential housing and who countered the general attitude of “Why build homeless people something nice—with their own bathrooms, for example—when they should be thankful to have a roof over their head?” The center also offered wraparound services on-site, such as primary care and mental health services. And unlike a lot of housing programs, the Cylar center served active drug users because Housing Works believes in harm reduction.

But not everyone wants to live in a place like the Cylar center. Regarding the Transgender Transitional Housing Program, Housing Works’ Lynn Walker points out that those clients are more comfortable out in the community at large, not surrounded by only other transgender people. To meet that need, Housing Works offers some clients individual apartments scattered throughout the city (a.k.a. scatter sites). “Clients seem to be more comfortable on their own,” Walker says in the film, adding that they’re expected to get out at least three days a week and connect with, for example, a job, school or other project. The important thing, she says, is that clients have a home with a bathroom, a kitchen, a clock—prerequisites for medical compliance. “The good thing is that it works,” she says, adding that “100 percent of clients in the Transgender Transitional Housing Program are virally suppressed.” (An undetectable viral load enables people living with HIV to live longer and healthier lives and renders it virtually impossible for them to transmit the virus, a concept known as treatment as prevention, or TasP.) Clients at the women’s program are also undetectable and usually achieve this goal within 30 to 60 days of moving in, says Annette Lacoot-Hylton in another of the films. “Housing Works is helping them do things differently,” she says, “so they don’t return to the criminal justice system. At least 92 percent of our women complete parole.”

Although Housing Works is still very much active, HousingWorksHistory.com does not cover anything beyond 2015. That’s because Browning, who has a full-time job outside of this archive, needed a finite end for the project. Will he or someone else continue the story? “I see a lot of importance and history in these documents,” he says, “and what would be a dream for me is that an institution like the New York Public Library would acquire this so that future historians can study and understand these things.”

Gavin Browning will speak about HousingWorksHistory.com at the Housing Works Bookstore Cafe in New York, 7 p.m., Tuesday, June 20. Titled “Community Archives, Radical Histories: Housing Works History & NYC Trans Oral History Project,” the event also includes Jeanne Vacarro and Elizabeth Koke. For more details, click here.

Editor’s note: This is an expanded version of an article in the June 2017 issue of POZ.

Comments

Comments