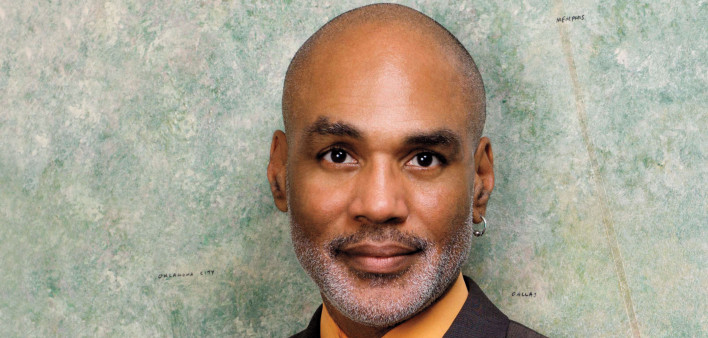

Phill Wilson, 65, was raised in the row houses of the Altgeld Gardens housing project in the far South Side of Chicago. “I don’t think anyone would say that I was a troublemaker,” he says, “but I do think my early childhood forecast who I would become as an adult.”

“I remember as early as kindergarten,” Wilson says, “I had a neighbor. I’m the oldest of four. She was a middle child in a family of seven or eight. The result being that my parents had more time to spend with me than hers did with her. We got to kindergarten, and there were all these things that I already knew how to do. I knew how to read and tie my shoes, and she didn’t.”

When his friend stumbled over some challenges, like tying her shoes, Wilson would step in to help. “Whatever the project was, I would finish and then go over and help her. It upset the teacher, and I didn’t understand it. But she would berate my friend, and that really bothered me.” The two were separated into different classes. “I said to my mother that it made me sad, because my friend was struggling, and I could help,” Wilson recalls.

Wilson’s bigheartedness and desire to be helpful grew as he matured. As an adult, he and his then partner moved to Los Angeles in the early 1980s, when rumblings about a disease affecting gay men were first heard. Friends started getting sick and dying. After Wilson and his partner both tested positive for HIV, they volunteered for the cause.

Before too long, Wilson was asked to head the STOP AIDS Project in LA. He has served as the AIDS coordinator for the city of Los Angeles, the director of policy and planning at AIDS Project Los Angeles and on the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS, among myriad other positions. In 1999, Wilson founded the Black AIDS Institute (BAI), the only national HIV/AIDS think tank focused on the Black community, and served as its president and CEO. Throughout his entire career, Wilson passionately and steadfastly battled stigma and bigotry in the fight against HIV, and his work was recognized both nationally and internationally.

After nearly 20 years of service, Wilson stepped away from BAI in December 2018. “My personal crowning achievement is that I think I was able to demonstrate how to say goodbye,” he says. “I was able to appreciate my own limitations, to read the tea leaves of the signs of the times, to embrace that for every time there is a season. I’m very proud of the growth and accomplishments of the institute in the time since I stepped down.”

Wilson is now working on a memoir and coming to terms with a life lived focused on HIV/AIDS advocacy. “I’m trying to process my own PTSD,” he says, “40-plus years of suppressed trauma and grief and compartmentalization that there was no time and

no space to address.”

After giving so much of his life to service, Wilson is now concentrating on himself. “For me, it’s been important to lean into gratitude,” he says. “Those of us who are aging—I think it’s a requirement for us to celebrate, and it’s disrespectful to all our friends [we lost] not to.”

Comments

Comments