The house and ball scene is back in vogue. Although they shot to world fame over three decades ago with the documentary Paris Is Burning and Madonna’s megahit “Vogue,” ballroom dance competitions and their communities have returned to the cultural spotlight by way of the reality show Legendary (Megan Thee Stallion is a judge) and the drama Pose, which was set in AIDS-ravaged 1980s and ’90s New York City.

Since balls remain popular among LGBTQ folks of color, the events offer a unique opportunity for HIV outreach. New diagnoses among Black Americans fell 10% between 2015 and 2019. But a closer look at the data reveals disconcerting trends. Gay and bisexual men, for example, accounted for 69% of the total 36,801 new HIV diagnoses in 2019. That same year, Black Americans represented 13% of the U.S. population ages 13 and older but 43% of all new HIV diagnoses. New diagnoses among Black gay and bisexual men ages 25 to 34 increased 12% between 2014 and 2018.

To learn more, we spoke with Maven Lee, 32, an HIV advocate in St. Louis who has been living with the virus for a decade and has been involved in ballroom and kiki events across the nation. (Kiki is a more youth-oriented twist on ballroom.)

Lee is the Midwest overseer of the House of Nina Oricci, which was featured on Legendary and has members in Missouri, Chicago, Detroit and Indiana. You can watch Lee in season 2 of the reality series The Kiki Show, now available (for free!) on Vimeo.

How did you get into HIV advocacy?

I was part of a house here in St. Louis called the House of Efficacy, and it was centered around HIV prevention and outreach more than on walking balls, which is a little bit unusual. I started volunteering at an HIV organization called Project ARK on behalf of my house, and I started learning about HIV. I ended up getting a job at the organization as a peer advocate.

I thought I knew it all and was protecting myself. I was dating around and things like that, and there was a situation when everything I knew went out the door. I trusted someone, and I was vulnerable, and, honestly, that’s how I ended up becoming positive.

It was an interesting situation, because I was working at an organization that tells you this is what you’re supposed to do [to stay HIV negative] and how you handle situations. But none of that mattered when my feelings and emotions and heart came into the conversation and I trusted someone. I then realized that I had to nuance what I was being taught when I said it to other people because it’s not that simple. We need to speak to folks like they’re real human beings because it’s not as easy as “Protect yourself. Use a condom.” When you talk from real experience, you start to say things differently.

Did working in the HIV field prepare you for the diagnosis?

Absolutely. At one point, I was disappointed in myself and angry. And folks made me feel this way. They were like, “How dare you make this mistake? You’re supposed to know better.”

I also felt like me becoming positive opened the door [for me to] be a positive light for so many people. I’m able to live a very healthy life, I’m undetectable and I’m doing well. Who’s to say this was not something I’m supposed to experience?

How long did it take before you started disclosing your status?

When I was told my results, the first thing I did was call my house father and call my grandmother and father—he’s my uncle but raised me as his son. But I don’t think my family understood. They didn’t necessarily judge me, but they haven’t talked about it since.

Maven LeeCourtesy of Maven Lee

Like a week later, I participated in a retreat for Black and brown men who have sex with men, and we were all sitting around and sharing information, and for some reason, I felt compelled to say, “Hey y’all, last week, I found out I was positive.” This was 2011. So I disclosed that day. I saw how difficult it was for folks I know who have HIV—the hurt and confusion of having that conversation every time they met someone—so for me, I wanted to get that [over with] immediately. It was a relief to me.

You’re also a singer and auditioned for shows like The Voice. Are you open about your status in those situations?

I’ve wondered if my HIV status has caused producers [not to put] me on the shows. I’ve gotten to the last stage of auditions on almost all the singing shows and never get past that round. To be honest, I’ve even been told that sharing my status has cost me certain opportunities in mainstream media. That was a pretty hard thing to hear someone say.

Do you discuss HIV on The Kiki Show?

I do. In the beginning, it’s what they focus on. There are four others who are HIV positive on the show.

It was filmed in Philly—the first season was in Atlanta, when I lived there—the second season is individuals battling against each other, unlike regular balls, where it’s house competing against house. And it’s folks from different regions competing in runway, vogue and tag-team performance.

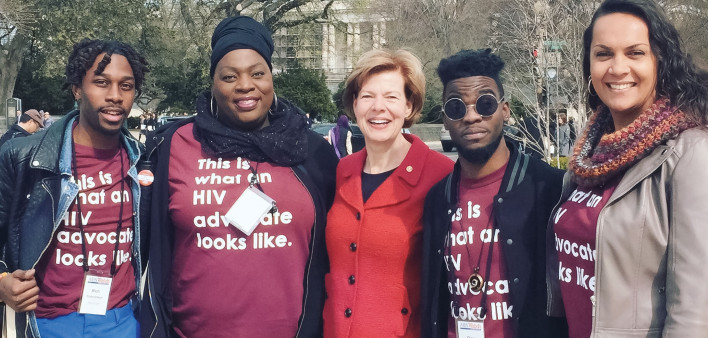

While in Atlanta you also participated in AIDSWatch, the advocacy event for which folks travel to Washington, DC, to meet with elected officials. And you were going by the name Omar?

I identify by various aliases. That year I represented both Georgia and Missouri. I was particularly excited to be an ally for trans issues that year.

Tell us about your history in the balls.

I’ve been walking balls for 12 years. I’m legendary for the category of runway. To be a legend or icon, you have to be deemed as such. I’ve walked in every major ballroom city in the country and abroad. Ballroom is everywhere.

I’ve been to balls in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Kansas, Nebraska, Chicago and Detroit. We have had some very successful balls in St. Louis. We have a mainstream ballroom scene and a kiki ballroom scene—they’re a little bit different. In St. Louis, we treat the kiki ballroom scene more as a practice for the mainstream scene. Our kiki balls are like 50 to 70 people.

In some cities, the kiki scene is almost bigger than the mainstream ball. New York’s kiki ballroom scene gets 500 to 700 people in attendance. Our mainstream ballroom events get like 200 to 400 folks.

You organized a ball in St. Louis during Black Pride last summer, and you’re planning events at historically Black colleges and universities. Does this overlap with your HIV work?

I consult with several LGBTQ centers and HIV service centers here in St. Louis. Some of the HIV agencies like to throw balls because lots of young LGBTQ folks of color come out to balls and pageants, so [it’s an opportunity] to get people tested for HIV and connected to services.

Has the ballroom scene changed during the past decade?

The community is evolving, and stigma is decreasing. Far more folks are open to sharing their HIV status.

Ballroom is beginning to shift into an era where even folks that are loved on the ballroom floor are being held accountable for stigma, bias and so on.

Have recent television shows such as Pose and Legendary affected the ballroom scene?

Honestly, some folks love the shows, and some in the scene feel the shows are inauthentic. It’s truly a mixture.

As far as influence, Legendary has elevated some folks in ballroom who weren’t known much before the show. And I think Pose has certainly given some folks in ballroom a reminder of its roots. To me, it really told some honest Black queer stories.

Comments

Comments