We’ve come a long way in the 30-year fight against HIV/AIDS. And yet one major battle remains in our quest to live normal lives with the virus: HIV discrimination. From medical centers to prisons and employers to schools, U.S. society is still saturated with stigma and misinformation. And this can drive people and businesses to withhold basic civil rights from the HIV-positive community. Fortunately, people living with the virus are armed with the legal rights and tools to fight back—but only if they know how to use them.

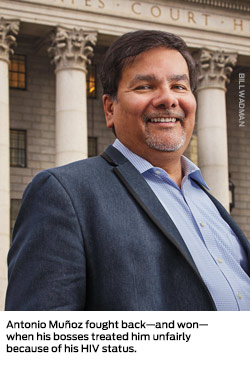

In April 2013, a New York City jury awarded Antonio Muñoz, an HIV-positive man, nearly $500,000 in federal court for being fired from his job. The lawsuit’s defendant, a boutique hotel called The Manhattan Club, had argued that its former employee was a lazy complainer unable to perform his duties. Muñoz argued that he was just a newly diagnosed guy trying to take care of his health. The legal system supported his claim that he was a victim of HIV discrimination.

Watch our exclusive video interview:

In that aspect, Muñoz is not alone. Nearly 63 percent of HIV-positive people in a Lambda Legal survey said they had experienced HIV discrimination when dealing with the medical community. Nearly one-third of the general population believes at least one myth about HIV transmission—for example, that it can spread via a drinking glass. And a Kaiser Foundation survey found that 23 percent of Americans would be uncomfortable working with an HIV-positive employee.

Indeed, the fact that people with HIV still have their civil rights violated is no surprise. But more people, like Muñoz, are fighting back in court—and they’re winning. Have you been discriminated against? Does it warrant a lawsuit? POZ talks with the experts and looks at three different cases to help you recognize HIV discrimination and prepare for a legal battle. Know Your Rights

Know Your Rights

First things first: Learn all you can about the laws most relevant to HIV discrimination. For a primer, Scott Schoettes, a senior attorney and HIV Project national director at LGBT litigation group Lambda Legal, spells out how HIV-positive people’s rights are protected under U.S. law. (Schoettes knows his stuff. He has defended dozens of cases, including Melody Rose, an HIV-positive inmate who won a settlement in 2010 for being denied gallbladder surgery while incarcerated. He also sued the U.S. State Department for refusing to hire an HIV-positive soldier for foreign service duty in 2003, a ruling that forced them to change their policy.) Many HIV discrimination cases, Schoettes explains, are built on a combination of four federal laws:

The Americans with Disabilities Act (the ADA) gives federal civil rights protections to people with disabilities, allowing them equal access to all public places, services, facilities and employment opportunities. When it passed back in 1990, legislators put HIV/AIDS on the list of disabilities.

“Sometimes the clients I talk to think, ‘Well, I’m not really disabled,’” Schoettes says. “But anyone living with HIV is entitled to protection under the ADA, regardless of whether or not it’s dramatically affecting their ability to work or to function in their everyday life.” In fact, an amendment to the law in 2008 clarified that people living with HIV, whether symptomatic or not, are fully covered under the law.

The ADA guarantees equal access to: goods and services; medical care and other public facilities; privileges, such as the ability to raise and adopt children; employment, education and occupational training programs; and transportation. The ADA also protects HIV-negative people from discrimination based on the assumption they have the virus.

The ADA, however, only applies to public or private businesses that have 15 or more workers. Plus, the employer has to be aware that you have HIV—or at least some sort of medical disability—in order to be called out for HIV discrimination in court. That requires at least semi-disclosure to your employer.

The Family and Medical Leave Act allows full-time employees who have worked about six months or more and who are sick (or have a loved one who is sick) to take an unpaid, job-protected leave for up to 12 weeks, while still retaining their employer’s health insurance coverage.

The Fair Housing Act prohibits any landlord, real estate broker or other housing authority from delegating or refusing housing based on prejudices; it is similar in legal coverage to the ADA.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) was enacted by Congress in 1996 to help standardize insurance and health care procedures in the United States. Among other things, the law protects the privacy of your medical history and information. Under HIPAA, it is illegal for a health insurance company, doctor, co-worker or employer to disclose your HIV status to anyone.

Schoettes predicts that another law will soon be a major player: Obamacare, or the Affordable Care Act (ACA), because it bars insurers from denying coverage based on a pre-existing condition.

In fact, Lambda Legal recently fought several Louisiana insurance companies for refusing to accept Ryan White funds as payment for insurance coverage. This May, HIV advocates also sued four Florida-based health insurers for placing HIV meds in their most expensive tiers. Define Your Discrimination

Define Your Discrimination

It’s often a challenge to recognize and prove when laws are being broken. Consider Antonio Muñoz. He was diagnosed with HIV in 2008, after about a year into his job at the hotel’s front desk. Between 2007 and 2011, he won an Exemplary Manager Award, earned several raises and got positive evaluations from supervisors. At first, Muñoz didn’t think he had to disclose. He just kept pushing along as a model employee.

However, when his health declined and his doctor prescribed Sustiva, a med that causes drowsiness and has to be taken at night, Muñoz knew he might be in trouble: He could no longer work the night shift, a position he had occasionally filled. He tried to take the pills and perform his job. But when his CD4 cell count didn’t go up, his doctor wrote a note to his employer explaining that he had a ”serious chronic medical condition” and could no longer work at night.

Muñoz should have been good to go at his job. That’s because the ADA states that employers must “reasonably accommodate” their disabled, whether that be providing a special telecommunications device for a deaf employee or, in Muñoz’s case, cutting an unhealthy shift.

When the Manhattan Club put Muñoz back on the night shift, it broke the law. When supervisors retaliated against Muñoz for complaining about it to human resources, it made matters worse.

By the end of 2011, Muñoz was fired after an anonymous complaint was made against him. (Interestingly, lawyers matched up the writing style of the unmarked note to his supervisor’s in a subsequent handwriting analysis in court.)

To illustrate how far the ADA’s protections go, look at the story of Greg Daniels, who wasn’t even fired from his job. He quit—and still won six figures in his 2003 lawsuit. Daniels had been working full-time for nearly three years as an outwardly HIV-positive clerk at a San Francisco CVS ProCare pharmacy. When the business merged with another chain, it got an influx of new customers and employees. At the same time, Daniels had to take a few days off in a short amount of time.

Supervisors said he was abusing the work policy, but Daniels argued that he had vacation days and needed to see his doctor to stay healthy and employed. When Daniels got a doctor’s note explaining that he needed an extra day off every week to take better care of his HIV, CVS flat-out said no. After he complained to human resources, his managers tacitly approved a new schedule but never followed through.

“After months and months of pressure and delaying tactics, I was sick a lot.” Daniels recalls. “I was nervous and having anxiety attacks. All sides of management were doing everything they could to make me look like a bad employee,” Daniels says. “Eventually, I just saw it as a losing battle, and I had to put my health above my pride and the job.” He quit—and then got educated on his legal rights.

Discrimination isn’t confined to the workplace either. Consider this third case: Sarah Franke-Bowling, of Little Rock, Arkansas, sued Parkstone Living Center in 2009, because it refused to take care of her HIV-positive father. Her dad, the late Robert Franke, was a 75-year-old former college professor and minister who had lived with the virus nearly three decades and who had always been open about his status. Parkstone reps believed that he posed a direct threat to the other residents and that they’d have to provide him with separate living and eating quarters, which they couldn’t afford.

Decisions based on this faulty reasoning broke both the ADA and the Fair Housing Act by denying Franke equal lodging, food and services, while ringing an obvious discriminatory alarm bell—it’s been common knowledge for decades that HIV cannot be spread through food or air. Thus requiring separate accommodations is an “excessive precaution,” which falls under the ADA’s umbrella of illegal discrimination.

After Franke-Bowling’s husband asked other assisted living centers in Little Rock to take Franke under their care, the family decided they had to file a lawsuit. Why? “Every single one of them said no,” she recalls. “This was bigger than we thought.” Lawyer Up

Lawyer Up

The good news is, since the White House adopted the National HIV/AIDS Strategy in 2010, the U.S. Department of Justice has set aside a special Civil Rights Division specifically dedicated to the ADA. The DOJ has also marked all HIV discrimination cases as “priority investigations” on its list.

A few examples of such legal cases: The U.S. government sued the South Carolina Department of Corrections for separating its HIV-positive inmates into different wards in prison. It has tracked down several schools for discrimination, and it even went after a small-town Rite Aid for saying it couldn’t give an HIV-positive man a flu shot because nurses needed “special gloves”—it then forced the store to pay the man nearly $10,000 in damages.

But figuring out when and how to file a lawsuit can get tricky. Sometimes, as in the above cases, the DOJ will take on a lawsuit pro-bono, particularly if it involves “places of public accommodation” like schools and hospitals.

Aside from the DOJ, legal advocacy teams, like the ones at Lambda Legal, the Center for HIV Law and Policy and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), are a good second stop in trying to parse out where your case stands.

“We’re looking for cases that can create a good precedent,” explains Lambda Legal’s Schoettes, who took on the Franke lawsuit. “That case was important,” he says, “because the HIV epidemic is aging and we need to make sure that the people who provide services to the aging population have a better understanding of HIV.”

“I didn’t realize that part of our role was to be spokespeople,” says Franke-Bowling regarding the case. “But we were willing to do that. For people who are discriminated against, they’re not just helping their cause [when they fight back], they’re helping so many more people.”

Such cases are called ”impact litigation” because they have the potential to change the course of discrimination history. They often make court records open and the names of their plaintiffs public to help bring awareness to the issue. Groups like Lambda Legal often choose envelope-pushing cases that the Justice Department may be reluctant to address—or cases made against the U.S. government itself.

HIV-positive people with a potential lawsuit may also hire a lawyer in the more traditional sense. That’s what Muñoz and Daniels did, and this legal option has its advantages. For one, thanks to HIPAA, HIV-positive people can keep their names confidential both when they file a case and after it goes through.

In addition, a lot of civil-rights oriented firms are willing to take on discrimination cases pro-bono too, if they think an argument is strong enough. In fact, a big part of a legal advocacy firm’s job is to refer HIV discrimination cases to private attorneys. Muñoz’s lawyer Gregory Antollino explains: “It’s always going to be private attorneys in general who are going to enforce these laws. It’s not an easy task. Most of these cases get dismissed, and many of them settle.”

Of course, as in any court case, you will have to prove you were wronged. To that end, you might need written records and people who witnessed the discrimination. Phone call recordings, emails and doctors notes can all be used as evidence.

“I had copies of everything,” says Daniels of his CVS case. “I think I won because I kept all the important records. I am beyond organized, and I think they were surprised.”

Muñoz and Daniels both took an important step by first going to their human resources office to make a formal complaint, long before lawyers got involved. In doing so, they were able to prove, in written documentation, that their poor treatment on the job was directly related to their medical disclosure.

One last bit of advice from Muñoz: “You need to have determination and to believe in yourself.” The average HIV discrimination lawsuit, if it does actually make it into court, will take an average of two-and-a-half years. Then, both sides can appeal the case, multiple times, which can draw out the already slow process of litigation.

For Muñoz, even though he has technically won more than $500,000 in the court of law, his legal battle remains far from over. The Manhattan Club says it will appeal. That means, even if Muñoz wins again, he won’t see any of his discrimination damages until at least 2016.

Muñoz says that it’s worth the wait—and that it’s not just about the dollars. “I didn’t want to settle,” he says. “I knew I had done nothing wrong, and I wanted to tell my story.”

Click here to read tips on filing an HIV discrimination lawsuit.

Click here to read our timeline of HIV discrimination.

1 Comment

1 Comment