|

| Sir Elton John |

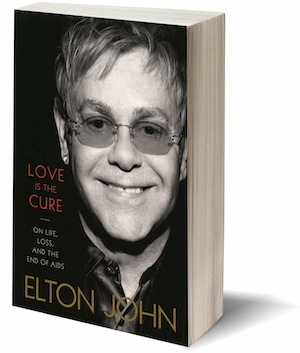

Generations ago, John Lennon said “all you need is love.” Today, Sir Elton John takes it up a notch with his newly-released paperback, Love is the Cure: On Life, Loss, And The End of AIDS. Part redemption memoir, part political manifesto, the book is the legendary British entertainer’s impassioned clarion call for others to stand up and fight the epidemic.

John wasn’t always such an outspoken advocate. In the 1980s and early 1990s, he was a rock star through and through: fantastically successful and wealthy beyond his wildest dreams. And also sinking into an emotional, spiritual and physical black hole. As a gay man living through the harrowing early years of the AIDS epidemic, he watched helplessly as cherished friends, such as Queen front man Freddie Mercury, died in the prime of their lives.

Despite the devastation surrounding him, he engaged in high-risk sex. “It’s no small miracle that I never contracted HIV myself,” he writes in his book. Cocaine and alcohol fueled the fire. He was also a compulsive eater and eventually a bulimic. “I was guilty of every single one of the seven deadly sins,” he writes, “except sloth.”

It would take an HIV-positive teenager from Indiana to hold a mirror up to John’s face. After John heard news reports that a boy named Ryan White had been refused entry into public school because he was living with the virus, he reached out. Relating to White’s humble upbringing and his family’s earnest and forgiving approach to Christianity, he was immediately taken with the boy and they formed a powerful bond.

White died of AIDS-related complications in 1990. He was just 18 years old. And yet in his short life he both inspired and educated a nation with his courage in the face of astonishing public vitriol. He also inspired a devastated John to get sober.

But the musician’s turn-around didn’t stop at simply quitting drugs and alcohol for good. Racked with guilt over not having contributed to the fight against AIDS, he went into overdrive to make up for lost time. He founded the Elton John AIDS Foundation, a grant-making organization that over the past two decades has raised and distributed over $275 million.

|

In Love is the Cure, John recalls his fellow champions in battling the epidemic, including Princess Diana and Elizabeth Taylor. He also describes his ambivalence over receiving his Kennedy Center Honors from President George W. Bush at a time when the White House was openly hostile to the LBGT community. The president would go on to impress the entertainer as yet another fellow advocate for fighting AIDS.

Vice President Dick Cheney, however, was not so impressed with John, maintaining his famous scowl in a moment of all-around levity as the malaprop-prone Bush referred to the song “Bernie and the Jets”—“It’s ‘Bennie and the Jets,’” First Lady Laura Bush corrected him—while bestowing John’s honors. John had, after all, recently lambasted the Bush administration as “the worst thing to ever happen to America.”

Storytelling aside, the book is most fundamentally John’s assiduous examination of the causes of HIV’s spread and his earnest plea for effective measures to counteract such destructive forces. He maintains a running theme throughout: The real villain is stigma.

The answer, he asserts, is love.

Providing further answers, Sir Elton emailed responses to questions from POZ and AIDSmeds about his book, his life, and his thoughts about AIDS:

POZ:

Many have argued that the oft-stated goal of an “AIDS-free generation,” or an “end to AIDS,” as you describe in your book, is overly optimistic and can cause the public to lose sight of the very difficult obstacles facing getting a handle on the epidemic, much less actually ending it. How do you respond to that point of view?

Elton John:

The goal of a world without AIDS is a call to action—not a guarantee. For decades, the news we have heard about the AIDS epidemic has mostly been about the suffering and death the disease has caused. I think it is incredibly important that the public realizes that the news regarding AIDS today is actually quite hopeful—so long as we build on the momentum that has brought us to this promising point. That’s why it’s important for people to know that we really can have an AIDS-free generation. What we’re missing are two things the public can help provide: appropriate funding and the will to see this through.

What, among the Elton John AIDS Foundation’s (EJAF) efforts, are you the most proud of?

From the very beginning, we understood that to fight AIDS, we must treat every person living with the disease with care and compassion, regardless of who they love, where they live, or how they contracted the virus. I am very proud that we have stayed true to this principle over the past two decades. Throughout EJAF’s history, we have not shied away from providing help to those who have needed it the most—gay men, sex workers, prisoners, the homeless, and injection drug users. We continue to proudly help society’s most marginalized groups who are at the highest risk of infection.

What more do you imagine your friend Princess Diana might have done in the fight against HIV had she lived?

Few people influenced public opinion towards AIDS as Princess Diana. She reached out—literally—to those who were dying of the disease at a time when people still feared contracting the virus from toilet seats. We were discussing the idea of Diana joining EJAF as a global ambassador when her life was tragically cut short. Had Diana lived, I have no doubt that she would have continued her life’s work of showing compassion and bringing attention to the voiceless and forgotten.

You describe Ryan White as “a true Christian, a modern-day Jesus Christ.” A particularly moving moment in your book is when Ryan’s mother forgives the lawyer who led the fight to keep him out of school—at Ryan’s funeral, no less.

The qualities that I find most inspirational in Jesus Christ are universal love and forgiveness, which were exactly the qualities that Ryan and his family so beautifully demonstrated throughout the many extremely difficult challenges they faced.

You have famously stated that Pope John Paul II was guilty of genocide for his opposition to condoms, and in your book are at least somewhat less critical of Pope Benedict XVI. How do you react to Pope Francis’ recent statements about gays and abortion? What do you think we can expect from him when it comes to fighting HIV?

Pope Francis has made some very promising remarks, and I welcome them. While words are important, action is even more so. In 2001, then-Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio washed and kissed the feet of 12 AIDS patients—an amazing and beautiful gesture. That is the kind of compassion I hope we see from Bergoglio as Pope. But most importantly, I hope we see him endorsing the use of condoms to stop the spread of disease.

|

| Sir Elton John and Ryan White |

You are very frank in the book about your past addiction to substances, and how Ryan White’s death inspired you to turn your life around and throw your energies into fighting HIV/AIDS. How have you used your experience with addiction to inform EJAF’s work as it pertains to fighting substance use as a driver of the HIV epidemic?

My own personal experience has taught me the importance of treating people—including drug users—with love and compassion. I was a drug user. I very easily could have contracted HIV. I have absolutely no right to pass judgment on anyone else. I think anyone who looks at their own experience will realize that few, if any of us, are in a position to condemn others for the choices they make. Drug users deserve access to prevention and treatment of HIV as much as anyone else.

How can entertainment itself, be it popular music, film or television, contribute to the fight against HIV?

Everyone has a voice, and some are fortunate to have voices that echo. I encourage those with many followers to use their platform to fight stigma against those living with HIV or at risk of contracting it.

In your book you describe the chapel in your home in Windsor, England, where you go to remember people you have lost. There is a wall there, full of plaques commemorating friends who have died of AIDS. What sort of emotions do you have when you look at that wall?

I look at that wall and I miss my friends. I also think of the tremendous human potential lost because of AIDS. My friends were mostly young men in the prime of their lives. What else might they have accomplished had they lived?

A big push in the United States in the past three decades has been to convince the public that AIDS is “not a gay disease.” And yet 63 percent of all new HIV cases are among gay and bisexual men. How do we tailor our messaging to make sure heterosexuals know they are at risk without downplaying how disproportionately gay and bisexual men are affected?

We talk about the “AIDS epidemic” as though it is one epidemic that affects all people equally. But in reality, the AIDS epidemic is made up of several different epidemics among certain groups: gay men, sex workers, prisoners, and drug users, for instance. That said, anyone can contract AIDS, and all kinds of people do: gay and straight, men and women, rich and poor, black and white. We need to spread the word that HIV/AIDS can and does affect everyone, but we also need to pay attention to the populations most devastated by the disease. It’s a delicate balance, but a necessary one. We need everyone to see the human side of the AIDS epidemic while also doing everything we can to curb infections in the communities hardest hit.

Much has been said lately about how the generation of gay men who survived the worst years of the AIDS epidemic are now suffering from shell shock, including depression, drug use, loneliness and suicide. As a member of this generation, what would you say can be done to help these survivors?

We have to help survivors cope, and one important way to do that is by working as hard as we can to end AIDS in our lifetime. We have already made so much progress, which I hope provides survivors some peace.

Many AIDS service organizations have struggled to raise money in recent years as the sense of urgency about the epidemic has waned. How would you characterize EJAF’s fundraising outlook?

EJAF has been fortunate to have maintained healthy levels of fundraising, and we were grateful to recently receive a $1 million gift from our long-time supporter Lily Safra. But it’s certainly true that urgency about AIDS has waned, and this is very problematic. Because we’re so close to ending AIDS in our lifetime, we’re right at the point where we need more attention given to AIDS, not less, and more funding given to fight the disease, not less. Anything short of this could have a devastating impact on our global progress.

You tell a hysterical story in the book about Elizabeth Taylor: generous to a fault, and swearing up a storm. What do you suppose drove her efforts to fight HIV?

Elizabeth was a class act. She simply believed that everyone’s life had value. In the 1980s and 1990s, she saw many of her friends become ill and die of the AIDS, often very suddenly. She once said, “I kept seeing all these news reports on this new disease and kept asking myself why no one was doing anything. And then I realized that I was just like them. I wasn’t doing anything to help.” I think her motivations were as simple—and powerful—as that.

You write repeatedly of the need to love and respect one another, to fight stigma against people with HIV, to battle homophobia and biases against drug users, sex workers and the like. How do you try to promote all of this in your own life and work?

Whenever possible, I try to speak out against stigma. This was the case when I traveled to Ukraine to speak out against the treatment of people living with AIDS there.

You state in your book that there is no greater power than government to fight HIV. What do you see when you look into the future of HIV in an era of U.S. budget cuts, sequestration and a feverish conservative push to shrink the government?

President Bush was the major force behind the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which has saved millions of lives around the world. Bush is a Republican and he was able to gather support for PEPFAR among other conservatives. Ending AIDS has always been a bipartisan issue, and I believe members of both parties can and should work together to end the epidemic in our lifetime.

Comments

Comments