The HIV community has its share of documentaries, but it seems more so after the world commemorated 30 years of AIDS in 2011. Many of those outstanding new films—We Were Here, How to Survive a Plague and United in Anger, to name just a few—look back at the heroic contributions of both people living with and affected by the virus.

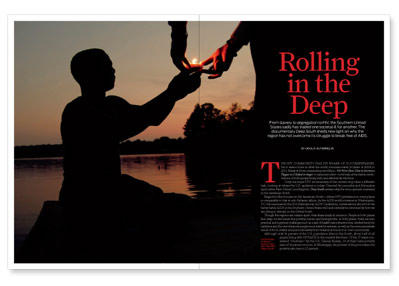

Only one major HIV documentary of the current crop takes a different tack, looking at where the U.S. epidemic is today. Directed by journalist and filmmaker (and native New Yorker) Lisa Biagiotti, Deep South reveals why the virus spreads unabated in the American South.

Biagiotti’s film focuses on the American South—where HIV prevalence in some places is comparable to that in sub-Saharan Africa. As the AIDS world convenes in Washington, DC, this summer for the XIX International AIDS Conference, conversations about how we better battle AIDS in the Southern United States will undoubtedly be informed by how we are doing so abroad, in the Global South.

Though the regions are oceans apart, they share much in common. People in both places face deep-rooted issues like poverty, racism and homophobia. In both places, there are also practical and logistical challenges such as a lack of health care infrastructure, limited funds for medicine and the vast distances people must travel for services, as well as the more immediate needs of food, shelter and personal safety from violence at home or in one’s community.

Although only 36 percent of the U.S. population lives in the South, about half of all people living with HIV/AIDS in the country live there. Of the 17 states considered “Southern” by the U.S. Census Bureau, 13 of them have poverty rates of 16 percent or more. In Mississippi, the poorest of the poor states, the poverty rate rises to 21 percent.

In the film, Kathie Hiers, CEO of AIDS Alabama, best sums up the facts: “[In the United States, the South has] the most people living with HIV/AIDS, the most poverty, the most sexually transmitted infections, the most people without health insurance, the most vulnerable populations, the fastest growing epidemic, the least access to health care, the highest mortality rates and the least resources to deal with this crisis.”

By making a film about the known drivers of the U.S. epidemic, Biagiotti helps us to have a deeper understanding of how those drivers intersect, why they persist and what can be done to overcome them.

|

| From top: Lisa Biagiotti; Kathie Hiers; two retreat attendees; Josh (right) with his “gay family”; and Monica Johnson |

I had been in Jamaica looking at the intersection of homophobia and HIV infections rates. [While doing research,] I came across the statistics [that told that a similar story was happening] in the South. I was shocked.

In June of 2010, I had just wrapped a documentary so I decided to go on a road trip. I had never been to the South. I have since driven 13,000 miles across it. Every one of my dozen trips there has been eye-opening.

The issues [that drive HIV] seemed to be much more entrenched than I first thought. Searching for HIV in the South was like using my GPS to find fragile communities.

What was the most challenging aspect of making the film?

[Finding people to tell it.] How do you tell a story about an invisible population? How do you tell a story that no one really wants you to tell? [Sentiments such as] “Here’s another Northerner coming down and exposing us” were definite challenges. It probably would’ve been a lot easier to write about this with anonymous subjects.

I had done some assisting on documentaries, but this was my first film as a director. Had I known that I was going to tackle a subject that nobody wants to talk about and that is largely invisible (although the stats prove its existence), I don’t know if I would’ve done it. But it seemed like the logical next step for me.

There were many times I just wanted to give up. I couldn’t have done it without people in the film like Josh, Kathie, Tammy and Monica, who are so brave. [Their resilience and strength inspired and helped drive me.]

Tell us about the plot.

The film follows three story lines broken up by mini stories that look at broader political, social issues in the South.

One of the main subjects is a young gay black man named Josh. He is 24 years old. He leaves the isolation of his traditional home in the Mississippi Delta to visit his “gay family” in Jackson for a barbecue. We meet his gay “father,” who’s not really his father but acts as a father figure, and all of his gay “brothers.”

Josh was at a crossroads in his life where he was wondering if he should finish school or move to the city. He felt really alone in his hometown. I found that a lot among young gay black men in the South.

Many of them experienced some sort of trauma that led to a period of sexual ambiguity that in turn led to HIV infection, attempted suicide and a life of isolation, except for those who had access to the cities. In the cities young gay men can connect with [others in] the gay community.

Monica Johnson, founder and executive director of HEROES (Helping Everyone Receive Ongoing Effective Support), and Tamela “Tammy” King, program coordinator of HEROES, are from northern Louisiana. Every year they have an HIV retreat in a state park. It’s mostly local, but people from Louisiana and Alabama and Mississippi come to it. It’s a small retreat that focuses on connecting people, bringing them to this place where they can talk about their lives—and HIV.

I thought the retreat would focus on drug regimens. It didn’t. It was more like the support groups we see in urban areas. They did a bunch of exercises and activities to break down the tension. By the end of the retreat, [most participants] got to the point where they felt it was OK to talk about HIV.

I documented how all of their friends and their sons helped out, whether cooking or setting up tables. For small agencies across the South, the funding isn’t there [to have large staffs].

Kathie Hiers is the CEO of AIDS Alabama. She spends 120 days a year on the road giving talks at conferences and up on Capitol Hill. Even now we joke, the first thing I ask her on the phone is, “Where are you?” because she’s never in Birmingham.

I needed to put the Southern AIDS epidemic in context with what’s going on at a national level, and that’s what Kathie does for us in this film. She travels extensively, repeatedly making her pitch, hoping to gain equitable funding for her region.

Why is the HIV rate acute in the South?

A perfect storm of factors drive HIV in the South. You have a crumbling health system and a repressive society. In general, the South is not the healthiest place in the country, and HIV is just one of the many health issues affecting the region.

Couple that with a culture of denial where you can’t be gay, you can’t have HIV and you can’t go against this really rich and beautiful and complicated culture. In the end, if you can’t fit in, what you really have to do is leave. You have to leave for services, you have to leave to be who you are. But not everybody can leave.

And sometimes people want to be themselves without leaving. So you have these underworlds or dual realities happening in the South. Pastors rail from the pulpits against homosexuality, and so does the culture at large.

A lot of conversation around stopping HIV is wrapped up in two words: prevention and behavior. I want to challenge what they mean. HIV is not merely about that time you didn’t have a condom, you had sex and got HIV. Josh was molested as a child. How would you behave if you were molested as a child or if you had some childhood trauma? The secret and repressed nature of the South allows these things to happen.

Stigma also contributes. Although there may be a health clinic around the corner from you, if you don’t want people to see you go into that clinic you’re going to drive 70 miles away to go to the next one. It’s exhausting [and expensive].

I met an infectious disease doctor in Mississippi, and he said something that was really telling. He said when he started as an infectious disease doctor he never thought that prescribing the cocktail of drugs would be the easiest part of his job. He has to make sure that his patients show up for their appointments, that they are refrigerating their medicine and that they have electricity.

The South has enough numbers [of people living with HIV/AIDS] to justify [increased] funding. The ways that we are trying to end the epidemic are not conducive to getting people into care. To link people to care and help them stay there, we need to [first] address poverty. People need a home, and they need food and support. That’s what Kathie talks about. That’s what Monica and Tammy talk about. [The things that help us fight AIDS are] really basic.

What did you learn making this film?

The South is a really interesting place. Southerners love family and community. Every time you show up, people are genuinely excited to see you again.

The American South is such a beautiful but fragile place. The people there are just slogging it out day in and day out. They’re doing the best that they can with limited resources. It’s inspiring.

If I were from the South and I was exposed to the environmental risks surrounding this disease there, I would be just like the people in the film. This disease shouldn’t be a matter of geography. But it is.

Across the South I saw small organizations resigned to the fact that they’ve always been poor, always had to do it themselves. [There is a sense of] “This is just how we live.” There’s a sense of real resignation across the South.

As Kathie says, “The South does not have the activist movements like those in San Francisco and New York. We’re quieter, we’re polite, we’re not rude.” People are not screaming, not marching on Washington. They’re just making do, they’re just getting by because HIV is not their only problem.

“Am I going to be able to feed my kids?” “Is my job going to be there next week?” These are the kinds of things that people have on their minds.

It isn’t that people aren’t trying. I followed people in this film who were really trying, and I saw people across the South trying all the time. In fact, all of the stereotypes I held as a Northerner have been debunked.

There’s a strength and resilience among Southerners that impresses me every time I go down there. [I can’t help but wonder what would change with the right resources.]

The film will be screening at the E Street Cinemas in Washington, DC, during the XIX International AIDS Conference on July 24 at 7 p.m. and on July 25 at 3 p.m. and 7 p.m. Go to deepsouthfilm.com for more information.

3 Comments

3 Comments